Just who are these people who put together computer games? They spend hours and hours locked away in rooms with very little light, too much food and very strange records. They're hardly human at all, are they? Jim Douglas quashes the oldest myth in the industry, and talks to some very normal people.

Simon Dunsten and George Stone from Ram Jam wander through the building site next door to their office without batting an eyelid. The cacophony emanating from somewhere beyond the large blue screens must surely be an enormous distraction. "You get used to it," says Simon.

Sitting in The Coffee House - which isn't a coffee house at all, it's a pub - Simon and George chatted to me about politics, world affairs, trivia, alcohol, and - er - oh yes! Games design.

Situated in the very centre of the 'busy' part of London, just off Carnaby Street and about fifteen seconds away from a Big Record Company and a Big Film Company, the Ram Jam Corporation appears every bit as grand as its neighbours.

When I talked to them, they were recovering from the rigours of finishing Dandy, Electric Dreams' Gauntlet-alike. Although there was a final glitch that still needed fixing, the whole conversation seemed like a huge sigh of relief.

George found the Trivia coin-op, which burbled away, too much of a temptation. Forcing change into the little black slot in a most unsettling manner, he bashed away with a surprising deal of precision, answering questions about which I was clueless.

While George thought loudly, Simon explained how he came into contact with his first computerized gadget. "It was a con job! I'm an artist really, but I like the idea of putting pictures on to a TV screen. It's like another medium. If you think about what happened when oil paints were first invented, there was a revolution in the way people thought about pictures. It's the same with computer graphics."

|

George, meanwhile is complaining vociferously about the time limit given to answer the questions. He sits down, credits used up. "Previously, I used to write technical brochures and leaflets around the time the electronic chip first arrived. It was also the time of the TRS80: 'Any colour you want, so long as it's green' and 16 glorious K."

George is carrying with him a 'portable' telephone, which would be very impressive if it wasn't quite so enormous. As it is, he is forced to wear a large waist-coat sort of coat over his shirt acting as a sort of harness.

The Ram Jam Corporation has built itself quite a reputation as producers of high-class software: Valkyrie 17, Dandy, Twice Shy, Explorer, Terrors of Trantoss. Their offices are impressive in a lived-in sort of way. Leading me through the dimly lit corridors, Simon announced that he would take me to meet a programmer. A man of his word, that's Simon.

Kevin is anything but a typical programmer. Looking more like someone-who-should-be-very-famous-indeed than a boffin. He sits at a graphics tablet, beavering away in a casual sort of manner with a science fiction game the Corp is producing. "It's only in the baby stage at the moment," he admits "but it's looking good."

Simon and Kevin begin discussing some technical ideas involving concepts so baffling they may as well involve time travel. It turns out - to my relief - that they were talking about time travel after all. The game features differing realities, which the player can visit, depending on the events s/he encounters elsewhere in the game. Confused? You should be.

RamJam don't believe in storyboards. "Storyboards are useless!" says Simon. Instead, they produce mock-ups of screens on the computers, and work through their problems that way. "After all, a computer screen bears very little relation to a piece of paper. I mean, it's flat, OK, but the colours and all the rest are completely different."

Their adventures, which were the real inspiration to get involved with the computer business in the first place, are created using the 'BIRO', their own adventure writer. BIRO is currently being used to finish Three Days in Carparthia, a game that RamJam assures me isn't going to go the same way as some other notable adventures for which everyone waited so long.

"People have a very blinkered attitude when it comes to quality. Simply because they don't know what is possible, they are prepared to put up with an awful lot of crap."

The toughest program they have had to produce was Dandy. "Just because of the space limitations on the computer." says George.

RamJam find themselves in the privileged position of not having to wander around, offering their services to any hapless software impresario who happens to be passing. "It's a small business, and everybody seems to know what everybody else is doing. We've worked with quite a few people."

Also in the pipeline is Shadow Warrior - a true-to-life Ninja game (whatever a true-to-life Ninja game is) and a diplomacy simulation in outer space. Apparently, "Activision want something on nuclear physics."

What do they think, in general, most programmers want to be? Simon: "Loved." George: "Rambo."

Joey is a man of mystery. He uses no surname! Along with his mate, Glyn Williams, he set up Solid Image one year ago. Since then, well, exactly what have they been doing?

Both studied computer science, and then Joey then became involved with ex-Buzzcock Pete Shelley, whose album he enhanced with a computer program which added graphics in time with the beat. From there, Joey moved to Bug Byte software for a while, and settled - temporarily at least-with Island Logic, the people behind the much revered Music System. Joey worked on the C64 Midi.

Next came the Polyscan Project. Sounding like a top secret government operation - actually, not a million miles away ... it involved Joey and Glyn working away for months and months in order to produce three-dimensional rotating objects on 8-bit computers.

|

|

The development of Cholo was a very complicated business - |

Working design for a Cholo robot |

"Yes, it's a bit of a tall order," Joey admits "and after a few months, Island decided that they just didn't want to spend any more money, and so they closed it down."

Joey first began programming as a break from studying Law at university. "Someone said there was money in it, but don't believe it." I don't believe it.

Solid Image find that they are only now beginning to make a name in the industry, and as a result their work involves quite a lot of doing the round of companies, seeing if anyone was interested in what they had to offer.

Cholo is their first big break. It's a wire-frame graphics epic being produced for Firebird. They produced a vaguely Elite-style 3D graphics system, whcih could create both indoor and outdoor scenes, and then visited various people. Firebird were very interested and that's how it happened. That was about six months ago. At the moment, the finishing touches are still being added.

Mark Eyles reclines in his chair, black coffee in one hand, trusty Filofax in the other. The ex-maths-teacher-made-good leafs through the delicate green pages that match his Next shirt rather too well, and owns up to being responsible for Back to the Future and Hijack.

Eyles first came in contact with computers in the earliest days of the ZX80, the wonder machine that could do minuscule, but nonetheless astoundingly important things while looking closely related to a primitive calculator.

Unemployed after his one-and-a-half year tour of duty as a teacher, he began constructing hardware add-ons for the ZX80 for the then newly established Quicksilva. At the time, the company was almost entirely hardware based, and led the field for a considerable period. After its takeover by Argus Press, Eyles left the firm and took up holography.

He retained firm ties with Quicksilva's ex-boss Rod Cousens who set up Electric Dreams and Rod suggested he get involved with Back to the Future.

Mark picks up the story: "It just snowballed from there. I used to write to companies, asking if they were interested in games designs, and things like that."

Since then, he seems to have worked for just about every major company in the industry. He drops names like Ariolasoft, Melbourne House and Activision with the familiarity of a man who knows 'the biz'.

"I must have done around twenty-five designs this year and they've kept me pretty busy."

Busy is probably some way short of an exaggeration. On top of his new role as an ideas salesman, Mark is expanding his interests in holography and is also helping to write a children's book with an artist friend.

Crossing his legs and turning the pages of his burgundy bible once more, Eyles tells the story which all programmers will know so well. "Back to the Future was a bit of a rush. We knocked it out in about two months flat. We really wanted about twice as long to do the film justice, but the deadline was pressing ..."

The word according to Eyles regarding the birth of a game is as follows: "There are three ways you can go about getting the idea for a game. First, there is your licensing deal. Then the software company may come up with an idea which it feels would make a good game. Finally, there will be an original idea from yourself."

Licensing deals are a dangerous breed. They often involve a large amount of money being expended in order to get hold of the name of the film/TV series/book, and the games are often rushed out to coincide with an advertising campaign which is operating at the same time as the film/TV series etc.

Back to the Future was a prime example of this syndrome.

The software house's ideas are a little safer. Sometimes, as in the case of Hijack, the company (Electric Dreams) will approach a 'team' (Mark Eyles) with words to the effect of "OK, we've had a great idea for a new game. Why don't we produce a program based on a hijacking?"

The third method is much akin to a freelance writer, or first-time novelist, and involves approaching a software house directly for which you feel a particular style of game is suited. "It's a better to think about who you are going to see, and producing a set of ideas tailored for them, rather than simply visiting everyone with the same set of ideas."

Once an his idea has been accepted, he'll draw up a storyboard, giving an idea of how the game should play, a map if necessary, and a representation of how the screen should be laid out.

"Then," he shrugs, "it can go one of two ways. Either you sit in on the programming, or you don't. If you've done a decent storyboard, though, there shouldn't be any nasty surprises when you see the finished game."

Aliens, the program on which Mark was working at the time of writing, was designed almost entirely from the ideas and story in the script of the movie. Work was started on the game long before the film was released.

Now the design is less cluttered, and only one character will be in view |

Mark now makes up dummy screens for his games on an Atari ST, in order to give the programmers and their respective bosses an idea of what the screen should look like when playing.

Which program is he most satisfied with? "Well, there is some stuff for Ariolasoft that is still to be announced, and Hijack for Electric Dreams. Each game is a different challenge. Each presents its own set of problems."

What is he working on at the moment? "There's a project for Melbourne House that I'm not allowed to talk about," he announces, his voice trailing off toward the end of the sentence, and turning over a page scarred with numerous red notes. "And there's Aliens, of course, for Electric Dreams, and Centurions and GoBots for Ariolasoft."

And away he goes, Clarks shoes, Filofax and all. A man with so much on his proverbial plate it will probably never be empty, who expresses an affinity for taking risks, and who has found an almost unique niche in the games world. One of a handful of individuals who earn their crusts from games designing, as distinct from programming.

Denton Designs - formed a year age out of the remains of Imagine Software by John Gibson, Dave Colclough and John Heap - must be the most sought after contract coders.

Denton were the people behind Shadowfire, Enigma Force and Frankie Goes to Hollywood and have just released, again for Ocean, The Great Escape.

They have a reputation for being very secretive about their games designs, and are regarded as one of the most innovative software production houses around.

Their latest is Double Take for Ocean. It's a 3D stunning weirdo graphics/strange plot epic which sounds terrific.

Design Design: (l to r) David Fish, David Martin Welch, David Berrisford and Stafford |

Graham Stafford follows the blueprint for programming success - if there is such a thing - reasonably well.

He became interested in electronics at an early age, through his school's Commodore system. This led him to buy and build a UK101 machine in 1979.

After this, Stafford moved to university, became disillusioned and, with a few friends, started up Design Design in Manchester.

After releasing a number of titles independently Design Design now concentrates, it seems, on contract programming for other houses. Nexor was their last release under their own label.

Currently they are working on Nosferatu for Piranha, and Kat-Trap for Domark.

"My favourite program out of all the stuff so far is On the Run. The oddest was certainly Poddy 2112AD, which involved a character a sort of K9 creature would follow around."

At the time of writing, Stafford was deeply immersed in problems with Nosferatu. "It's a very, very big game. And it's very involved. I'm getting memory problems over and over."

Stafford, married to a primary school teacher and four cats, though not necessarily in that order, lives in a one-hundred-and-ten-year-old cottage which is set into a hillside.

He's also one of those ghastly people who can manage to eat a lot and not show it.

Fergus NcNeill is virtually unrecognisable. For a long time he was instantly identifiable as a marginally shambolic figure, who could be seen wandering the streets of Hampshire in a Marillion T-Shirt, jeans, fluffy beard and open shirt.

Fergus: hippy backlash |

So why the new image? "I was fed up of appearing in pictures where I looked like a hippy. I can't stand hippies."

Initially seeking comfort from a micro when his social life foundered: "a ZX81 was my first girl friend" - whatever that means - "and it went on to kill off anything that may have remained of social life, too."

A self-confessed smart-alec at school, he collected 'a load of O levels' before moving to college and dropping out after about one month. He was also offered the honour of being parted with £12 of his hard-earned cash in order to receive a piece of paper from MENSA. He's a clever man. He decided it was a waste of money.

The process of creating a game is reasonably ordained by the constraints of time and money. Operating in probably the most relaxed manner out of all the people mentioned here, Fergus and the Delta 4 'crowd' like to think of humorous situations before problems. "If you have a door with fifty-seven combinations, and you then try and build up a joke around it, you're going to have problems. If you get your humour sorted out first, it's easy to make problems along the way."

Delta 4 is essentially six people. Fergus is backed up by: Judith Child, a storyline person, Stephanie Stranger, a co-author on the game scripts, and Jason Sommerville is currently working with Fergus on the Denis Wheatley games, Murder Off Miami and The Malinsay Massacre. Andrew "SPUD" Sprout is their new 'public face' and administrative person.

Between them they must be the most overworked team in the business. Fresh from The Boggit, they're just completed The Colour of Magic for Piranha from the Terry Pratchett novel, there's the Level 9 work - which Fergus won't discuss fearing repercussions from non-disclosure agreements - the Wheatley titles and his own follow-up to The Boggit.

Another pet project is to do an adventure with a Bladerunner-type SF feel. "Society's totally fallen apart and you play the hero - the only bloke left with any humanity." Fergus turns out to be a big Harrison Ford fan.

All this and he's half way through his first novel.

Dave Lowe is a busy, busy man.

When I spoke to him, he was in the middle of a berserk period, in which he was programming the music for the 128K version of Starglider from Rainbird and playing in a band every night. He's one of a very small number of specialist programmers who produce music tracks for computer games - Rob Hubbard and David Whitaker (Glider Rider) are others of the select 'band'.

After producing the sound track for titles like Rasputin and Buggy Blast, both programmed with the 128's three channel sound synth, the Starglider track will be the first 128K game track made up entirely of sampled music.

Being first bitten by the computer 'bug' in the heady days of the ZX81, Dave is a professional musician. It sounds a rather exciting life: "I've been to most places around the world, Europe and America a couple of times. The problem is, you don't make any money."

So exactly how does he go about making the Spectrum make such wonderful noises? "Well, I worked out all the routines that I needed while programming the sound for a game called Rasputin, so I use those."

Sampled sound is another matter. For this, music must be played in a studio, recorded on to tape, digitised and then squished into a computer. Clever stuff, eh?

Although most of the micro music for computers Dave works on is still of the 'standard' variety - using the machine's in-built sound chips - he prefers sampling: "There's just no comparison."

"Writing for a computer is very similar to doing songs for bands" - he has worked with Scoby Smith, and Repro - "except that most of the tunes are only about 14 seconds long." He uses a CX5 and DX7 synth to produce the sounds, and you may find the occasional RX11 drum machine lurking around.

Dave says that to sample about 16 seconds of sound took 170K on the ST version of Starglider. "We tried it on the Amiga to start with, and when it took up about 420K, we realised that we would have to sacrifice some quality, in order to fit it into the computer." The 128K+2 version is somewhat shorter.

David Bishop isn't a programmer. He is a games designer, as he is at pains to point out. Along with his 'partner in crime', Chris Palmer, (who does have a bit of programming knowledge), as part of a firm called Tigress, he has worked on a number of hit titles, such as Deactivators and Golf Construction Set, both for Ariolasoft.

Bishop got involved in games design through working in the Games Centre, a now-defunct specialist board and war games store in central London.

|

Deactivators is a case in point. It's such a devilishly twisted idea it could only have been thought up by someone like David, who's steeped in games designs and board game scenarios. The key to producing a great finished game, David reckons, is to match the right programmers to the right game design.

"Some are more capable of producing certain aspects of programming than others - whether it's graphics, or 3D scrolling or whatever."

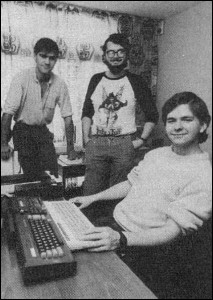

The ODE team get down to some serious triviality, and smile at the same time |

David Pringle - boss of Trivial Pursuit authors ODE - could hardly be described as having a stereotype programming background. After attaining a First at Edinburgh University, he moved to Oxford, and took up a position as a research physicist, taking a doctorate in the subject, and staying on.

He got to use mainframe computers a lot for analysis into things technical and fissionism. Here he met Gareth Blower, now the senior programmer at ODE.

None of the founder members had used a micro. The programs would have to be more tightly written, and a long time was spent familiarising themselves with the medium. Their first program was based on the classic Shakespeare play, Macbeth. Hence title for the company - Oxford Digital Enterprises (ODE, geddit?)

Their first 'hit' was RMS Titanic released in April by Electric Dreams.

Latest project is Trivial Pursuit for Domark.

Generally, Pringle says, there isn't much point spending more than about six months on a game unless you have a sure-fire winner on your hands. The structure for game design is very simple: one person will be assigned the duty of watching the project, and he or she will follow it through from start to finish. "This helps keep some kind of continuity."

"We always try to look for something that will set the game apart from anything that has gone before," Pringle says. "In Titanic, for example, we developed the wire-frame graphics, with broken lines, simulating what sort of visibility you could expect under water."

Geoff Quilley is the man responsible for producing the graphics on all of ODE's games. He began working on 8-bit machines, and then moved on to the Atari ST to do the graphics for Rainbird's Pawn. Now he's back with b-bit computers again. "I think he found it tougher working with the Trivial Pursuit board than the Pawn screens."

Although he says that it took quite a while to become recognised in the industry, Pringle says that companies are now beginning to come to them with ideas, as opposed to the other way round. "Domark approached up with the idea for Trivial Pursuit," he says, "after we had met them at the PCW show earlier in the year."

Pringle claims he's a perfectionist, but admits that all games software is a compromise. "Being from an academic background, you are used to always striving for the best but you've got to learn to meet deadlines."