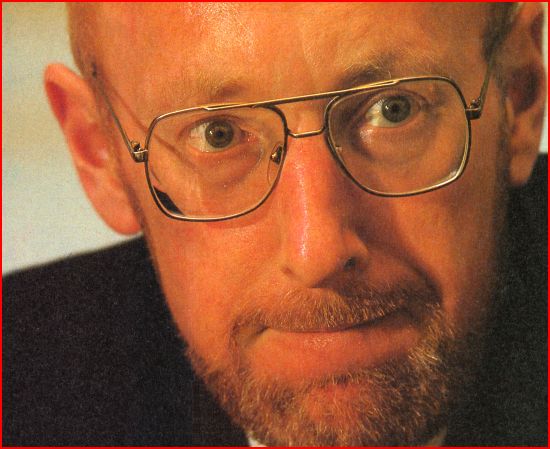

Is Sir Clive Sinclair a new age techno visionary or a deluded crackpot? A business incompetent or a consumer genius? Or none of the above ... Graham Taylor interviews the man who gave this magazine its name

Sir Clive Sinclair admits he was wrong. Wrong about the consumer market generally, and wrong about the QL in particular.

In the past, sometimes angrily, at other times somewhat wearily, he would defend every product and every marketing decision Sinclair Research ever made. On occasion it seemed he hoped to make black white by repeatedly declaring it to be so.

Now he's not only ready to admit the mistakes of the past but actually eager to do so. Such admissions seem a kind of therapy.

Like the optimist he declares himself to be, he is looking enthusiastically towards the future.

On a personal level, he is more open, friendly and charming than ever before, full of enthusiasm and keen to explain himself.

In the aftermath of the £12m deal with Amstrad - £5m cash and £7m in machines - we talked first about the Spectrum. Still an astoundingly popular computer despite its great age and obvious failings as a games machine.

"It was originally intended as a machine to teach computing," he admits, "and the games market was rather secondary. Of course it turned out the other way around but that was not the original intention."

I wonder whether he was actually disappointed at what happened. He says no. "Not at all, I didn't plan it and I didn't particularly want to get into the games market, but it was an interesting business.

"I just don't think as a company we understood it very well."

"If Alan Sugar can |

In fact, some time before the Amstrad deal, Sinclair had admitted the importance of games and had been working on a second new machine (the first which leaked to the press was the Loki) was codenamed the LC3, which stood for low cost colour computer. The machine was designed but later dropped.

"It was a complete colour computer, entirely on two chips - very much like the Japanese Nintendo machine but many years beforehand." The Nintendo is a dedicated games console, much more sophisticated than the Atari VCSs of old, currently selling bundles in Japan and the USA, and attracting attention from the likes of Alan Sugar, amongst others.

If the machine was designed so long ago why on earth didn't Sinclair Research make it? Sir Clive seems to choose his words with greater care. "The company got distracted as it were - I ceased to run the company on a daily basis, around that time Nigel Searle got involved and he was more interested in sophisticated machines - he went for the QL."

A pause follows - "I think the QL was a good bet but it didn't work out very well because the market for it wasn't as big as we anticipated, and we had early teething troubles."

The failure of the QL to attract a mass audience was something that surprised not only Sinclair Research but nearly all of the computer press as well. To some extent all of the powerful 68000 based home micros are having problems finding a market even now. What, I wonder, was Sir Clive's view now: "I think I have an explanation. I wanted to do the project that became the QL on the Z80, some or most of the engineers and Nigel wanted to do it on the 68000.

"I couldn't see the point of that because it seemed to me you were paying a lot of money for the chip and I couldn't see what you were going to be able to do on it that you couldn't already do on the Z80. The truth was there was nothing you could do on the 68000 that you couldn't do on the Z80. Sure, it was a bit faster in principle and this, that and the other but it wasn't like that in practice ..."

Certainly it is true that the best Spectrum software is far better than any of the QL software and Sir Clive agrees. He seemed keen not to sound as though he was trying to escape his responsibility for the QL error. "That's right. I'm not saying that I wasn't swayed by the others when they thought that this was the way to go - we all made that mistake. Looking back there was no need to go for 68000 technology.

"We just haven't found a way to use the 68000 that gives any extra benefit to the customer."

He thinks now that other companies may be similarly disenchanted with the 68000 noting that at the Chicago Consumer Electronics Show "Commodore weren't even showing the Amiga."

Was there any truth in the rumours floating around prior to the Amstrad deal of a new QL with disc drives instead of microdrives? "No, there was a program internally to do a QL-type machine, that's to say based on the same chips, but with disc drives. It wasn't really a QL though and it was a much more expensive machine."

Talking of microdrives in an interview full of admissions of various kinds of failure they are one area Sir Clive still defends strongly despite their bad press. "I'd defend them absolutely - I think they were a marvellous approach."

Over the past couple of months Sinclair User has been covering Loki, a project Sinclair Research had to create a Spectrum-compatible Amiga-bashing machine for under £200.

"Loki was a product under development before we sold out ... chip designs were under way but there was still quite a lot of work to be done on specific specifications. Basically, we thought if we could do an Amiga for under £200 with decent graphics there'd be a big market. I wasn't actually convinced of that. There was a danger of running into the same trap as the QL of not giving people what they actually needed.

"I still think the LC3 was the best approach".

Was Loki now abandoned? "It is so far as we are concerned because we sold the rights to 'Spectrum' technology to Amstrad. Even if we wanted to go on with it, which we certainly don't, it would not be our legal entitlement."

To an outsider, the Amstrad deal still seems clouded in mysteries - what can and can't Amstrad and Sinclair do?

In what sense would Amstrad have rights over Loki - because it would be Spectrum compatible? "That's right what they bought strictly speaking was the current products in the market but partly the 'know how' embodied in those products. Sinclair Research is specifically excluded in future from using Spectrum technology in new products which is fine, because it's not what we want to do."

The Loki papers are still sitting somewhere in the depths of the company, Amstrad has no rights to it because it was a future product but Sinclair cannot do anything with it because being Spectrum compatible it would infringe Amstrad's legal rights.

I get the vague impression that Sir Clive himself probably doesn't know precisely what the possible ramifications of every part of the deal are.

But then, I don't think he cares. His interests mostly having moved on. But what about Pandora, which last I heard was a Spectrum compatible machine? Sir Clive offered the idea to Amstrad. "It was originally a design using Spectrum technology and flat-screen technology that we thought Amstrad might be interested in. We offered it to them on that basis ... they had a good look at it and were not interested for quite straightforward reasons ..."

Well, Amstrad don't like new things, I suggest. Sir Clive laughs, "That's what it amounted to yes ... it was new and untried and not their cup of tea and I think it was wise of them. Their business is based on taking what works and sticking to what you know. Ours is breaking new ground which is risky but that's what we enjoy.

"There is now a problem with Pandora however. Since now they've turned it down it can no longer use Spectrum technology. We have to rethink our policy there.

"I think it's all for the best in a way, I think Pandora was getting bogged down anyway."

More evidence that for him the whole Amstrad/Sinclair deal was as much about freedom as it was about money. "We were getting a bit bogged down on the Spectrum, we were victims of our own past. lf we ever did a new machine we were more or less obliged to make it Spectrum compatible - the same trap as IBM. By selling off the entire range we're freed of that, we can start again and think again."

I ask about the options for Pandora now. Would it use some other proprietary operating system like CP/M? "We've never taken on somebody else's operating system and I don't think we will ... this is all just what I think. I don't have a plan yet." But he is still keen on the portable project. " My belief for years and years right back to the days of Sinclair Radionics where we had an internal project for a portable computer was that that was the way computers ought to be.

"I still want to go after that market and get out a product which meets that need. Obviously, there are portables but I think you'll agree that they are all compromises of one sort or another."

It is difficult to see exactly what Sir Clive is after that isn't practically answered by rechargeable batteries and a big LCD display.

"Agreed, there are all sorts of machines about and I must have looked at every one of them. But none of them make me think crikey, that's it! I see them and they are all wrong in some way.

"To me a portable computer must be totally portable and no trouble to use, and it mustn't cost too much to run. Rechargeable batteries are an anathema you never get round to recharging them. The power has got to last for ages - I mean really ages."

I remain unconvinced and wonder how many people there are wanting to do non-games things, really needing the kind of ultimate portability Sir Clive sees as fundamental.

"You've obviously got to think in terms of probabilities. The computer that is stuck to the desk or kitchen table is a dead end for computers to be really useful they've got to move with you. And they've got to work without the need for print and paper. To do that they've got to be with us all the time."

As far as Pandora in particular and computers in general are concerned, Sir Clive is known not to favour disc drives, because of "their bulk, weight and power consumption." Neither does he rate CD Roms (using a silvered disc like a compact disc to store data instead of music): "Aside from not being able to write on them, which will change, the access time is still very slow. You can make some improvements but it's mechanical and that's going to look increasingly bad." Sir Clive's money (literally) is in solid state media - the wafer drive project which is currently filling much of his time.

Barclays Bank has already put up some £2m investment money towards the wafer-scale project. "We've got the team together and now we're going after the second-stage backing. We've proved the technology and we are the only people in the world who have a working wafer we can demonstrate.

"What you have is a wafer of silicon a few inches in diameter and instead of chopping that up and putting all the bits that work into packages and then putting them all together again on a circuit board, you keep them on the wafer. The problem is that you've got to have some system to test for the good areas. Essentially we divide the memory up into blocks about the size of an ordinary chip and put a bit of extra logic on which uses a mathematical algorithm to connect up the good chips and not the bad. If one bit fails you can power-down and reconfigure it so it has an extended lifetime."

The implications of the wafer system are awesome, apart from cheapness of manufacture there is a potential memory size. "The amount you can get on a wafer is truly staggering, the first wafer we've made is half a megabyte. That's quite small, but it's still quite big for one piece of silicon. We should be able to achieve something on the order of 20 or more megabytes on one wafer - a couple of hundred million bits of information."

Since the deal with Amstrad, Sir Clive's projects now revolve around a number of separate companies. Whilst Pandora will be a Sinclair Research product, the wafer project is being handled by a new company called Anamartic. This firm will be selling shares to raise funds and will sell wafers to Sinclair Research for use in Pandora. When did he believe there will be a product incorporating the first fruits of the wafer project? "Next year sometime," he said without hesitation. A Sinclair Research product? "Not necessarily, that's not certain," he says hesitantly. His answers seem to reflect his complete confidence in the viability of the wafer but doubts over which company will be first to use it.

"There is a very strong chance that we may sell Amstrad wafers, I think Alan Sugar is likely to have some products for which they would be ideally suited - I hope to keep in touch and I like him very much."

Which brings us to that deal. He says it came "out of the blue" a few weeks before it was announced, and he had no idea of it even at the time of the 128 launch (about eight weeks before). There was another deal on the table, a cash injection operation which would have had the advantages of not requiring redundancies - rumoured to have been with Timex - but it would, says Sir Clive, have been a "poorer decision" in not addressing the fundamental problem of the a sort of company Sinclair was trying to be.

Even so, Alan Sugar seemed to get the Sinclair products and rights very cheap £12m for a firm valued at over £100m a year before. It is said he has already made £6m from sales of Spectrums.

Although Sir Clive considers his answer carefully, the a strongest impression is that whilst he may agree, he doesn't really mind. The money wasn't the only reason for making the deal. "I think it was a good deal from his point of view but what you've got to remember is that the whole market got in one hell of a mess ... I mean nothing to do with us particularly ... everybody in it."

And for the most part everybody still is. Commodore, for example, is still losing a fortune every month.

"If Alan Sugar can make money out of it which he may do, well, fantastic, but we were losing money in it and there is no sense in doing that ...

"The truth was |

"We had the option to sell for good money and get out of a loss making business and that seemed to me a good move to make. When we started Sinclair Research we said that we weren't in the business of bread-and-butter products and that's where the games market was definitely showing signs of leading.

"We were in the business of pioneering, and if there is no pioneering to be done then it's time to get out and do some somewhere else."

So now he's starting afresh, returning to the original ethos of Sinclair Research - that of the inventive laboratory.

Is he happier now? "Oh, absolutely. We were getting so bogged down in run-of-the-mill products which isn't our field. We're not as good as Amstrad at that sort of business."

All this goodwill and confidence is a little unnerving. Wouldn't he be just a little bit disappointed if (as seems quite possible) Alan Sugar uses the Sinclair logo on a badged version of a games machine or something like it, given that he had originally seen home computers as an educational and useful tool? He smiles "I suppose so, slightly.

"But I'm very pleased from Britain's point of view that Alan Sugar is the one who's taken on the Spectrum. He's a very competent guy and a very brilliant guy and he'll do well. He'll do a lot of things better than we did.

"I'm not being humble, because I think there are a lot of things we will do better than he ever will. Britain will sell more computers and we will be free to get on with innovating and ..." he adds wryly "you'll have two companies to write about."

My final impression is that for several years Sir Clive Sinclair has not been happy with Sinclair Research The Computer Company.

He has been alternately a victim of extraordinary success and then of financial failure. Both have restricted his options.

Indeed he seems to have had increasingly little say in a day-to-day sense with what Sinclair Research was doing. By way of an illustration - I asked him about the MIDI standard interface incorporated into the Spectrum 128 - "What's that?" asked Sir Clive, genuinely confused. Then he remembered.

Now Sir Clive is back in control. Back in control of the sort of company he understands and wants to be part of - a small team of talented engineers and specialists, concerned totally with invention, with the new and untried.

He declares himself to be an optimist and that's just as well because he's hardly chosen an easy path - he's been ridiculed before, with the C5. He probably will be again. The difference is now Sir Clive is unburdened and relaxed enough to share the joke.

Discussing Amstrad's plans for the Spectrum I mention that sticking on a cassette machine on the side, an obvious cheap thing to make it more 'sellable' in the high street stores, is just the sort of thing which, however logical, it was impossible to imagine Sinclair Research ever doing.

Laughing Sir Clive agreed: "Oh no ...far too obvious!"