| The Sinclair Story |

|

SINCLAIR'S SUCCESS had always been based on being first with products, often aimed at a market that didn't know it existed. By 1979 there was a well established 'personal computer' market. Commodore had launched its £700 PET home computer the previous year. Apple and Tandy were also well known in the field. These machines were found variously in laboratories, and commercial and teaching establishments; not many people had a computer at home.

Sinclair decided that he would have to offer a product with all the essential features but at a greatly reduced price. In May 1979 The Financial Times predicted: "Personal computers will become steadily cheaper and their price could drop to around £100 within five years." Typically, Sinclair decided to do it in a few months!

The ZX80 - the world's smallest and cheapest computer - was launched at an exhibition in Wembley at the end of January 1980. It measured 9" x 7" and cost £99.95, or £79 in kit form.

In order to keep the price low the designers had to introduce some radical ideas to reduce vastly the number of components. The biggest saving was the use of a domestic television set as a screen and a cassette player as a program and data store. The machine had a Z80A microprocessor which was supplied by Nippon Electric; a large ROM, which contained a 4K-byte specially written Basic interpreter, the character set and monitor; and the interfacing circuitry.

The ZX80 was very much aimed at the person in the street wanting to know something about programming computers. Sinclair was convinced that people could be persuaded to buy the ZX80 but how to persuade them was the problem. The image of the computer at that time was somewhat Big Brother; clinical, air-conditioned surroundings; huge cabinets with reels of magnetic tape whirring to and fro. How would people relate such a frightening piece of equipment to the ZX8O? Why would they want to buy it for the home? Why would they want to buy it at all?

No one need have worried. The ZX80 was an immediate success; ten orders were placed at the exhibition in the first five minutes. The office in King's Parade was suddenly inundated with cheques; the switchboard was permanently jammed. Nobody had expected quite such a response and there was total chaos. Clive's immediate problem was to ensure that the company could cope efficiently both with the administration, and with the production of the ZX80.

Sinclair wanted to sell the ZX80 in the United States, although he did not expect to find an enormous market there because of the strength of the competition in the home computer field. However, a few weeks before the launch of the ZX80 in the UK he took it to the Las Vegas Consumer Electronics Show, and at the same time met Nigel Searle in Boston. Within a few days Searle had a new job, a new apartment and an office in Boston. He sold the ZX80 and later the ZX81 in the States from that office by mail order until early 1982.

Sinclair Research expanded rapidly; by September 1980, over 20,000 ZX80s had been sold. Clive Sinclair was determined to keep the company to a manageable size; he was all too aware of the need to try to learn from previous mistakes. Bringing manufacturing in-house in the days of Sinclair Radionics had seemed an excellent idea at the time, but the number of people they had had to make redundant had hurt him deeply.

By this time there were 12 employees at the King's Parade offices in Cambridge, six engineers still working at The Mill in St Ives, and Nigel Searle in Boston. To make sure that the company didn't grow too fast Sinclair had subcontracted all manufacturing. To begin with, production was done locally in St Ives by Tek Electronics. Components were generally of a much higher standard than they had been during the Black Watch fiasco, so there was less reason to manufacture products in-house. Eventually, as more and more were produced, the computers were made by Timex in Dundee; it is a testimony to all concerned that the return rate on the ZX80 was only one per cent.

Although the machine was so popular and sold so well, this was largely because it had no competitors. In fact it did have some drawbacks such as the lack of floating point arithmetic, a capacity of only five digits and an inability to handle separate files on its cassettes. The touch-sensitive - or sometimes touch-insensitive - keyboard was unpoular with users too.

But in spite of those shortcomings, the ZX80 had opened a new market sector which exceeded Sinclair's wildest dreams, so who was going to complain too loudly? In September 1980, the company launched a 16K RAM pack - an extra plug-in memory - to attach to the edge-connector at the back of the machine. There will be many who remember the well-known RAM pack problem whereby a slight breeze could upset the connection and an evening's work would be lost. Thank heavens for Blu-Tack.

The ZX81 was launched in March 1981. It contained a new chip, designed by Sinclair Research and manufactured by Ferranti - the world leader in uncommitted logic arrays standard chips which can be adapted to a user's requirements at the last stage of production. The new chip replaced 18 chips in the ZX80 and the machine now retailed at £69.95 or £49.95 in kit form. Sinclair also offered an add-on ROM to convert the ZX80 to the ZX81.

The ZX81 had a floating decimal point and scientific functions. It came in a sturdy black case and, if you used a colour TV, would produce black characters on a restful green background. It was a vast improvement on the ZX80. Sinclair also announced that he would be launching a small printer to work with the ZX81 later in the year.

Now that he had an improved machine and the promise of a printer, Sinclair decided to fight back at the government's scheme by offering his own half-price deal. Schools could buy a package of a ZX81 and a 16K RAM pack for £60; and he further promised that they would be able to buy the ZX Printer at half price when it was launched. That made the total cost of system £90, while under the government scheme the minimum a school could pay if it bought an 'approved system' was £130. About 2300 schools purchased the Sinclair package.

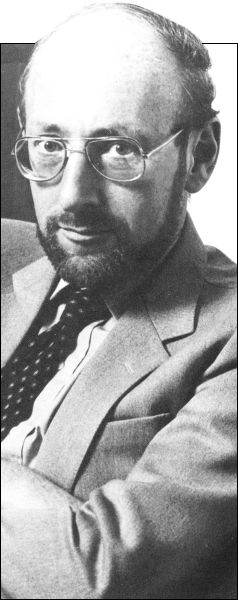

Sir Clive dons his running shorts |

The ZX81 received a very sympathetic review from David Tebbitt in Personal Computer World in which he keeps referring to 'Uncle Clive'. On the other hand: "Sinclair has been a bit cheeky in his advertisements. Under a column entitled 'New, improved features', he proceeds to mention three things that were included in the ZX80 when it was launched over a year ago!"

The ZX Printer was eventually launched in November 1981 at £49.95. Designed for the ZX81, it could also be used with the ZX80 with an 8K ROM. It was a very compact little printer using a special metallised paper, and would print 32 characters to a line and nine lines to the inch. You plugged it m to the edge connector at the back of the computer using a stackable socket. The print was clear and readable; the ZX Printer sold well.

The market gradually expanded. In March 1981 Mitsui approached Sinclair Research and towards the end of the year was granted exclusive distribution rights for the ZX81 in Japan. Mitsui was one of Japan's main importers of British goods, the range including Jaguar cars and Burberry raincoats. They planned to market the ZX81 by mail order at about £90 and aimed at selling 20,000 computers during the first year; there were no competitors.

By the end of January 1982, 300,000 ZX81s had been sold worldwide. In the USA Sinclair was selling 15,000 personal computers a month by mail order; American Express was selling thousands to a potential ten million customers. Then Timex was granted a licence to market both current and future Sinclair personal computer products in the US from mid-1982. They paid Sinclair a five per cent royalty for sales and bought the right to use the Sinclair name in the US.

In Britain, Sinclair signed an agreement to sell the ZX81 through the branching-out stationers and booksellers WH Smith. Today, when so many national stores - Boots, Dixons, John Lewis, and the rest - have sections devoted to matters computery, it is hard to remember what a breakthrough it was to be able to buy the ZX81 in the High Street. Not that other makers were far behind; the numerous retail outlets were just one of the ways in which the home computer created jobs. By February 1982 production of ZX81s was running at about half a million machines a year and the company had a turnover of £30M compared to £4.65M in the year ended March 1981.

One of the interesting side-effects of the ZX80 and ZX81 was the number of cottage industries that sprang up because of them, producing software, peripherals and publications. A ZX80 Users' Club had been formed before the ZX81 was launched; SYNC Magazine appeared in January 1981 to cater for ZX81 users; Learning Basic with your Sinclair ZX80 by Robin Norman, published by Newnes in early 1981, was one of the first books to develop Basic programming techniques on the home computer.

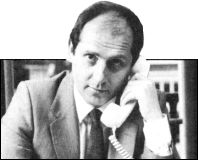

Nigel Searle in Boston |

Hundreds of small operations started to sell programs, books, extra memory, printers, sound generators and add-on keyboards for use with the ZX81. In January 1982 one Mike Johnston organised a fair for companies selling products for the Sinclair computers. Nearly 10,000 people turned up at Central Hall, Westminster, which has a capacity for only a few hundred; the police had to be called to control the crowds; 70 exhibitors took huge sums of money.

Both the ZX80 and ZX81 had been produced as learning machines; for the person wanting to find out about computer programming. Once people knew what they were doing they wanted a more powerful machine, and at first they had to turn to manufacturers other than Sinclair Research to find them.

Sinclair's philosophy - at least in retrospect - was to prepare the world for universal computer ownership in easy stages. Over 50,000 ZX80s had been sold, and more than six times as many ZX81s. As the market matured, the engineers were working away at the ZX82 (codename) which was launched as the ZX Spectrum in April 1982. The hardware was designed by Richard Altwasser, who later formed his own company, Cantab, and fell by the wayside in an attempt to market a computer called the Jupiter Ace. The software was written by Steve Vickers on contract from Nine Tiles Ltd - the company which had originally provided Sinclair Basic.

Production of the Spectrum started at 20,000 a month and Sinclair expected to sell 300,000-400,000 during the first year. There were two versions: the 16K sold for £125 and the 48K for £175. For those who preferred to work up in easy stages, an extra pack to increase the memory of the cheaper machine was available for £60.

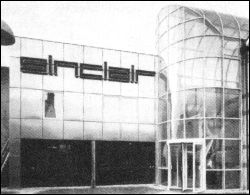

The Timex plant in Dundee |

In many ways the Spectrum was altogether a 'better' machine than either the ZX80 or ZX81, although some said its predecessor the ZX81 was superior when it came to finding out how computers actually work. Its chief advantages over the ZX81 were 'eight-colour graphics capability, sound generator, high-resolution graphics - smaller dots on the screen - and many other features, including the facility to support separate data files.'

At last, Sinclair Research was notionally able to compete with the BBC Micro and other personal computers; the figures in the table published in the ZX Spectrum leaflet were impressive. The ZX81 had been competing against the Acorn Atom; it could never have stood up against the BBC model A, the current Acorn competitor when the Spectrum came out. The Spectrum had a more versatile Sinclair Basic than the previous two machines; an improved keyboard replaced the unpopular - though cheap - touch-sensitive keyboard; it was able to generate and display graphics using up to eight colours; and it could be linked to other Spectrums to create a communications network.

However when Jim Lennox reviewed the new machine for the late lamented Technology Week, he was not impressed by the keyboard - which had been made to simulate moving keys by fitting a one-piece moulded rubber pad over a ZX81-type membrane keyboard, and which had a most peculiar feel to it.

The Spectrum was the cheapest home computer to produce colour graphics but the reviewer complained of the lack of facilities and 'found that the borders tend to wriggle in an irritating way'. It also had a small built-in loudspeaker which generated bleeps 'acceptable for games, but not much more'. And that, to Sinclair's disappointment, was about all the Spectrum was generally used for. The tone of the review was set in the first paragraph:

Sinclair's headquarters in Cambridge |

"After using it, however, I find Sinclair's claim that it is the most powerful computer under £500 unsustainable. Compared to more powerful machines, it is slow, its colour graphics are disappointing, its Basic limited and its keyboard confusing."

But never mind the reviewers; the Spectrum is without doubt the most commercially successful home computer ever. It was after the launch of the Spectrum that computer fever really took off; children were being introduced to computers at school and the very cheapness of the ZX80 and 81 meant that parents were prepared to buy them to give their children 'a good start in life'.

The place of the computer in the home was reinforced by the meagre provision in schools, where there was often only one machine between 30 pupils and thus insufficient opportunity for everyone to practise. What better solution than a computer at home?

But Sinclair observed another dimension: "The interesting thing is that as well as children being expert at programming, there is another expert group taking to it like ducks to water - retired people. The concept of it being peculiarly suitable to the young mind is perhaps wrong - it's the mind that's free of everyday burdens. The retired person with some time to spare can take to it wonderfully and it's giving a lot of people a new interest in life."

The launch of the Spectrum |

The first home computers had no software; to play a game on one you either had to make it up yourself or buy a magazine with a program in it - which was very good for the magazine industry - and type in the program before you could start to play. Now the Spectrum with its 48K memory was capable of playing very sophisticated games and there were companies starting up solely to produce them - often run by very young people who had learnt programming at school or from magazines.

In February 1983, WH Smith, who had been the Spectrum's biggest distributor, was joined by Boots, Currys, Greens - Debenham's in-store subsidiary - and John Menzies as Sinclair pioneered a change in the High Street. Many other stores such as John Lewis and the House of Fraser were supplied by Sinclair's UK distributor, Prism Micros. 200,000 Spectrums had now been sold by mail order, and by Easter 12-15,000 Spectrums were being sold per week in the UK. The Spectrum had also been launched in more than 30 countries worldwide.

You couldn't walk into WH Smith on a Saturday without being faced with shelves of software and mobiles and whizz-kids playing on the computers. What sort of computer you had became an important factor in playground status.

And where has it all led? Computer awareness has been generally raised; the dust has settled, much of it on the home computers, leaving a hard core of enthusiasts. The market is saturated; the craze is over. The computer is settling into a serious niche comparable with ham radio; the days of the CB computer are surely over.