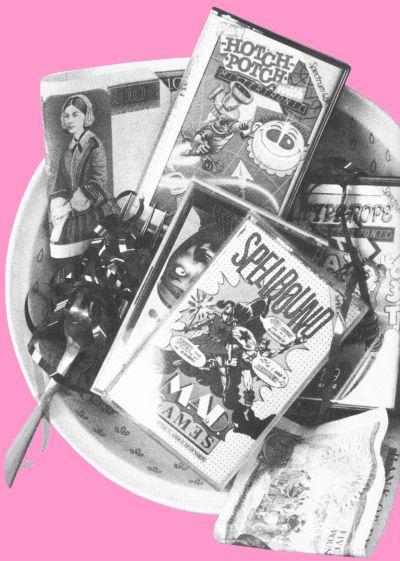

| Hit Squad |

GET THEM to take you out to dinner," said the editor. "And make sure they pay for it." So here we are, sitting round a table at the Ristorante Venezia, wondering why the head waiter's shoved us in a little corner at the back, well out of the way of other diners. What's on the menu? Mastertronic - well-grilled and served flambé at the table while you watch.

The tape-recorder sits in the centre of the pristine white tablecloth. Five Mastertronic people look at it nervously. The spools start to roll ...

Mastertronic is the budget software house to beat them all. It started operating about 18 months ago with a range of games, each costing £1.99. Reactions were hostile from virtually everybody. Magazines said the games were no good. Other software houses said prices like that would kill the industry. The founders of Mastertronic were portrayed as cynical businessmen, unloading cheap rubbish into newsagents and supermarkets to clean up fast.

The punters thought differently. Two quid is about the average amount of weekly pocket money doled out by British parents. You have to save up to buy games by Ultimate or Melbourne House. Mastertronic offers a quick fix at an affordable price.

Since those beginnings, Mastertronic has brought out 146 different games - if you count the conversions. That's sales of two and a half million worldwide. Figures like that are what other software houses dream about. They're why Mastertronic can afford to sell games as cheaply as they do. Oh, and Mastertronic is also the only British software house to have a firm sales base in the USA. Nearly everybody else who tried lost their shirt on the deal.

The waiter arrives, and John Maxwell, who controls the diverse groups of programmers working for Mastertronic, asks if there's anything special on the menu. The waiter, unable to understand him, departs in panic. "It is truly Italian here," says John, with satisfaction.

After a brief debate on restaurants with ethnic pretensions, the conversation turns to Spellbound, Mastertronic's first Sinclair User Classic. David Jones, who wrote the game, and also another 'tronic hit, Finders Keepers, is chuffed. "I got an Amstrad Accolade for Finders Keepers, but this is very nice," he says. "I'm trying to do adventure games in an arcade environment. There's a lot more to adventures than typing in strings of text. When I had a Tandy system I used to enjoy Scott Adams' adventures, but it wasn't the same when you had to use the Spectrum keyboard."

While David is explaining his attitudes to Spellbound, the rest of the party sort out the menu. Most decide the fillet steak with brandy sauce sounds about right, though PR Manager, Colin Johnson, ostentatiously fancies Eggs Florentine and "the ontercoatay wiv green peppercorns." Well, that's what it sounds like on the tape.

David Jones continues his explanation against the wall of noise which greets the arrival of the wine. "I was working for a very small company which was going down the drain because the wholesalers took no notice of us. Mastertronic seemed to offer the best deal - that was about a month prior to releasing Finders Keepers."

Mastertronic paid out £300,000 in royalties to their authors in the first year of operation. Although programmers can't expect much out of the £1.99 tag on a single game, the volume of sales makes up for that. The company has offices in the US, Germany, Italy, France and Belgium, as well as a distribution outlet in Australia. "At the Las Vegas show we have one of the biggest stands of any software company," says Colin, proudly.

David hints that he'd like to go to Vegas for a "nice little break." "You're too busy," says John, severely. The waiter asks David if he wants red or white wine. "Yes please," says David. That is the sort of mental attitude that makes him such an individual programmer.

John waves his glass in the air, painting expansive pictures of a Mastertronic Christmas. "We think Spellbound is going to be a number one," he says, "and there's going to be a helluva lot more people buying software this Christmas."

Mastertronic's target audience is identified as 8-15 year olds, with the main market in the 12-14 age bracket. But as John points out, "We try to cater for the whole market. It goes up to 60 years old."

That leads to the first assault of the evening on Sinclair User. "It strikes me," says Colin, suddenly struck, "that magazines talk about 'a Mastertronic game is ...' But the games are all totally different." It's true of course - there are so many different programmers that it's ridiculous to identify a single style. But surely Mastertronic knew that was likely to happen when the budget range was launched?

"Of course we did," says John, in a dangerously gentle voice, as the background muzak changes from Indian flutes to Fleetwood Mac's Albatross. "And at the beginning we needed to build a range quickly."

He's conceding that the first dozen or so games were not really very good. But the company is convinced that current products are much more advanced, and of as high a quality as anything at the £7 level, if not better and that's certainly the intention with the MAD series, at £2.99.

Sinclair User has certainly panned Mastertronic products in the past. How does a company react to such criticism? Some companies get extremely stroppy and threaten to withdraw all their advertising - though few actually go through with their threats. "When we saw your review of Action Biker," says Colin, "our immediate reaction was to go round and beat you up. That's the mark of true professionals." Later, he says the Spectrum version looks pretty rough if you compare it with the Commodore 64 version, "but taken on its own it's a credible game."

Soup and other goodies arrive. As invariably happens, one of the dishes remains unclaimed. Colin suggests running the tape back to see if anybody ordered it ...

It's hard to conduct interviews with a mouth full of onion soup, so the tape is switched off for a short while, prompting a flood of dirty jokes and scandalous anecdotes now we're 'off the record'. What isn't apparent in Hit Squad articles is the amount of time spent listening to the interviewees discussing the magazine. John has particularly strong ideas.

"Why don't some magazines do more in printing serious programming tips?" For some kids it's their one and only ambition in life - to be a programmer. It's something only magazines can do."

David agrees. "That's where I learned machine code," he says, "from magazines. Your Spectrum has Toni Baker, and you've got Andrew Hewson. Even if people don't understand it, it's nice because they can aspire to it."

"Like the Financial Times," says Colin, and we all splutter in our soup. The muzak abruptly changes to selections of Mantovani.

Having grabbed our attention, Colin proceeds to expound one of his pet hobby-horses. "As a Dungeons and Dragons player," he says, "I really can't understand why it can't be done on a personal computer." We discuss the problems of simulating the treacherous mind of a D&D referee, until John trumps us all with, "Wait until you see Magic Quest. It will be on the Spectrum in January - that's an attempt to do it."

The discussion lurches into an analysis of various fantasy adventures. Gargoyle's Cuchullain series is universally admired. "But here we are selling millions," says John, "genuine millions, worldwide, and you have people like Greg Follis, managing director at Gargoyle, happy with what they've got. I'm sure they could sell Dun Darach in America. Of course, with some of the rip-offs in the past, they've got cause to worry about the dangers. And that's a very sad thing."

So sad, that Mantovani yields to Richard Clayderman playing an extremely florid version of My Way. "That's a bit over the top, isn't it?" asks Colin. "I think it's rather good," says John, on the defensive for once.

After taking some photographs to demonstrate that 'tronic can afford a soup course, and enduring an earful from David about how magazines should credit the authors of games much more than they do, and after Clayderman gives up on Sinatra to regale us with Spanish Eyes, John explains that the difference between Ocean and Mastertronic is that Mastertronic "listens to the authors." Colin agrees. "There's no way the marketing department sits down and says 'we want a game with this and this and this ...

Shock! Horror! Alan Sharman makes his first move in the conversation. He's one of the big four at Mastertronic - there's Frank Herman and Martin Alper, Alan and Terry Medwhite. They're the heavy guys with the suits and two million years of experience between them. To emphasise the fact, Alan speaks extremely quietly.

"It happens sometimes, Colin he says. "It happened with Chiller. That was a marketing decision followed up by a program." Chiller was the game based on Michael Jackson's Thriller album and video. 'Tronic used the music without asking first, and got in a bit of a mess. "Um, yes," jokes Colin. "Michael Jackson didn't know a lot about that one.

Time now to bring in the one voice not yet heard - Alison, who runs the Mastertronic Club. The club has it's own newsletter, and members get a free game. She also deals with enquiries about the games. "There's an awful lot of kids," she says. "They write in with lists and lists of our games that they have. It's like a collection. And they write in with cheques from their mums and dads, which aren't signed. I never intended to get into computers. I wanted to be a trainee contact lens technician."

It turns out David wanted to be a quantity surveyor, Alan was a chartered surveyor, Colin did something mysterious in the music business, and John had a video company. Only John admits to ever having wanted to work with computers.

At long last the steaks arrive. They are massive - shaped like a cricket ball with a slab of pate on the top. "It looks like a huge beefburger," says Alison, awed. "Well, it's not from BT," says Colin "I can assure you of that." What?

Someone isn't quite sure if their chicken is what they ordered. Colin takes control. "No. Chickens have legs and feet. We know a chicken when we see one." The waiter is clearly terrified. "We rang up beforehand," says Cohn, "to see if they'd serve KP Skips with the meal." Skips are the obnoxious snack which promotes Clumsy Colin of Action Biker fame. "They showed us how they were made. It's revolting. You know those little plastic chips you get in packing materials ... they're exactly the same with added flavouring."

John tells a story about a beautiful woman he met in Sorrento who had five million brothers. David, meanwhile, is explaining to us how he's going to explain to his girlfriend why he's going to be late back home.

"Why can't you produce an Amiga with four Z80 chips?" asks John - one of those wonderfully loony concepts which crops up when people are feeling well fed and watered. "Because I've got a mouth full of food," says David. It turns out that David nearly got involved with the ill-fated Prism. He was asked to write the software to control Topo, the infamous robot that didn't work. "I sent them a quote for the work but they never replied."

Never insult programmers. David got his revenge in Spellbound - out of the 50 objects, only one is utterly useless. The Prism.

The gossip gets hotter and the jokes raunchier. We'll draw a veil over the final act, with the last portion of profiterol and the cold zabaglione, and what Alison did with her orange sorbet.

The final cost: £113, not including tips. Mastertronic foots the bill. Flash they may be - cheap they're not.