| The Sinclair Story |

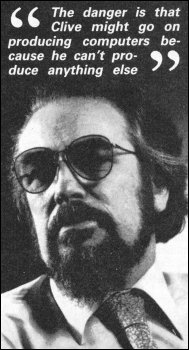

Bill Scolding meets biographer Rodney Dale, Sinclair brought to book? |

RODNEY DALE has known Sir Clive Sinclair for more than 20 years, ever since the Sinclair Radionics mail order operation was run from a disused bakehouse on Dale's premises in Cambridge.

Dale was involved with the development of the extraordinary and innovative Cambridge Consultants Ltd, which he later joined, forsaking his small publishing business. His path was to intersect with Sinclair's often in the years to follow. Later, when Dale became a full time freelance writer, he supervised the production of software manuals for Sinclair Research, most notably those for Logo.

The idea of writing the first biography of Sinclair came out of a discussion Dale had with Colin Haycraft, of Duckworth Publishers, in 1983.

"It emerged that Colin had been trying to get Clive's autobiography," Dale explains. "Clive had replied that he was too busy and in any case it would make him feel too old."

When Haycraft discovered that not only had Dale known Sinclair for some time, but would be interested in writing the biography, Sinclair was approached again.

"After much toing and froing Clive agreed that we could proceed. He wouldn't have consented," Dale adds, modestly, "to just anybody writing it."

Sinclair gave Dale several interview sessions and allowed him to rummage through his personal archive box. He granted, too, access to people in the company.

"'Granted' suggests that Clive had the right of veto over the manuscript," says Dale, "and I suppose in a way he did, though we agreed that he could later alter only errors of fact. He has seen the manuscript and hasn't exercised his right to change anything."

And how did Sinclair react to this 'warts and all' account? "Apparently he said, 'It's very accurate. I don't know where he got it all from.'"

Apart from the archives, Dale got it all from 60 hours of interviews with associates and employees of Sinclair. That, and ransacking libraries for back issues of Practical Wireless, Instrument Practice and other relics of the past. Filing cabinets and cardboard boxes crammed with cuttings line the walls of Dale's office.

The result, The Sinclair Story, is about as comprehensive as you could wish. More important, it is very enjoyable to read. Photographs of the beardless Clive, pages from his school exercise books and charmingly ingenuous adverts for his earlier products - 'easily built in a single evening' - help recapture the excitement and naivety of Sinclair's growing pains and the immature computer industry.

It's all there - Sinclair's volatile friendship with Chris Curry, the tragic involvement with the bureaucratic National Enterprise Board, the abortive attempt to win the BBC contract, the arduous development of the ill-conceived C5. Running through it all is Sinclair's obsession with miniature television, on which research first started in 1964.

Omissions are few, though it is surprising that Dale glosses over the beginnings of Sinclair Research and the work which went into the ZX80, especially given his meticulous approach to the development of the pocket calculators and the MK14.

Dale is taken aback when this is pointed out to him. "Yes, there is quite a jump," he agrees, scribbling a note in the margin. "There's nothing sinister in that ..."

Although The Sinclair Story claims only to be an account of Sinclair's business ventures, here and there we find the man behind the name peeping between the lines. Dale explains, "I asked Clive in an early interview how much he wanted it to be about the business and how much about him. He replied that he didn't want to suddenly appear as if from nowhere, but he did want to remain private. And that's what happened."

As to the future, Dale thinks that the home computer industry is likely to go the same way as the calculator boom of the seventies. "It's been a juggernaut. It's run away and crushed everything in its path.

"It's not an industry which attracts cautious people. Had it been so, perhaps the brakes could have been applied earlier rather than at the edge of the precipice."

Sinclair has been as guilty of that as anybody. "There are people within the company who individually think that caution and circumspection are a good thing, and that this has been overridden by success."

Drawing parallels with Sinclair's dogged determination to continue producing calculators long after the market had died, Dale adds, "The danger is that Clive might go on producing computers because he can't produce anything else."

Sinclair's venture into electric vehicles does not appear to be the answer, though Dale too was fired by Sinclair's enthusiasm over the C5. "One of the most extraordinary moments of my life was realising that there was something wrong at Alexandra Palace," he says, thinking back to that snowy day when the C5 was unveiled. "It suddenly flipped from a brilliant idea which was going to be a vast success to something which was very dangerous."

But, Dale concludes, "The world would be a poorer place without Clive Sinclairs around. They make enormous mistakes but they also make life richer."

Rodney Dale is author of a disparate volume of work, including a biography of Louis Wain, The Man Who Drew Cats; the modern folklore collection, The Tumour in the Whale; and The World of Jazz. With Ian Williamson he has co-authored Basic Programming and The Myth of the Micro.

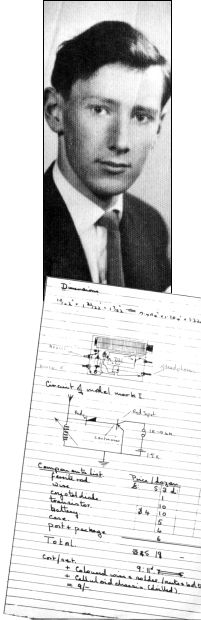

Clive Sinclair at A-level time; |

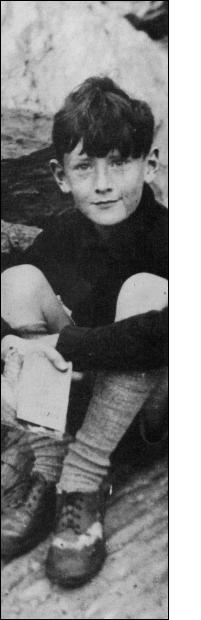

Clive's early days |

| The first of two extracts from Rodney Dale's Sinclair Story |

CLIVE MARLES Sinclair was born near Richmond in Surrey on 30 July 1940. His father and grandfather were both engineers.

Clive's brother lain was born in 1943 and his sister Fiona in 1947. The Sinclair children remember a particularly idyllic childhood. Clive came into his own in the holidays, for he loved swimming and boating and at an early age designed a submarine which owed as much to grandfather George's naval interests and Jules Verne as to the availability of government surplus fuel tanks.

Clive found the comparative freedom of holidays a necessary antidote to school; a time when he could pursue his own ideas and teach himself what he really wanted to know. A sensitive child with ways of thought and speech beyond his years, little interest in sports other than aquatic, he sometimes found himself out of joint with his schoolfellows.

He preferred the company of adults, and there were few places other than with his family where he could feel intellectual companionship. To some, the Sinclairs seemed to be unconventional, a family who spoke directly, frankly, and often argumentatively to one another as a matter of course - because not only was it more fun that way, but also, as Clive now says: 'You get more out of people by disagreeing with them.'

Clive went to Box Grove Preparatory School; he recalls it with affection, and was very upset when it was eventually closed. When he was ten, the school reported that it could teach him no more maths, and he moved on to the secondary phase of his education.

At about this time, his father suffered a severe financial setback. With Sinclair tenacity, he started from scratch - still in machine tools - and fought his way back in a remarkably short time. However, fighting one's way back is not without its effects on one's family, and Clive went to a number of schools for his secondary education. Taking his O-levels at Highgate School in 1955, and S-levels - in physics, and pure and applied maths - at St George's College, Weybridge.

Mathematics - that perfect, concise language - had always interested him deeply, and he had barely become a teenager when he designed a calculating machine programmed by punch cards. Because he wanted to make the adding as simple as possible, he did it all with 0s and 1s. 'I thought that was a great idea. I was really amazed to discover that this was a known system; the binary system. That discovery disappointed me deeply; I thought I'd made my fortune ... but I was very pleased with the idea.'

As a teenager, he also 'discovered' electronics. He had always been fascinated by things miniature, and he carried this interest into his electronic designs, seeking to produce ever more refined and elegant circuits, using smaller and smaller components. The state of his bedroom - a mass of wires - was a family joke, but from it came amplifiers and radios for his family and close friends, and an electrical communications system for their hideouts in the woods.

He worked hard at school, particularly on subjects he was keen on, reading and absorbing far beyond the required level. If he wanted to learn something, he did so very readily; he had - and still has - an incredible facility for assimilating information. The converse is true; at school he had little time for subjects which did not interest him. While still at school he wrote his first article for Practical Wireless; it was published; heady stuff.

As an antidote for working hard, Clive and his friends were wont to hold wild teenage parties. A friend of his from a strict Catholic family recalls that one Christmas Eve, after a few drinks, he said to Clive: '"I'm off to church; I've got to go because I'm in the choir", so Clive said he'd come along with me, and we staggered into the choir stalls and Clive just joined in with his fine bass voice. Not bad for an atheist!'

When he left school just before his eighteenth birthday, there was no reason why he should not have gone to university - except that he didn't want to. He knew from experience that what he wanted to learn he could find out for himself.

C M Sinclair's Micro Kit Co was formalised in an exercise book dated 19 June 1958 - three weeks before the start of his A-levels. In this book we find a radio circuit, 'Model mark I' with a components list: 'cost/set 9/11d + coloured wire & solder/nuts & bolts + celluloid chassis (drilled) = 9/-'.

He had been delighted to find how cheap components were if bought in bulk, and that there were such things as call-off rates. He also realised that to sell big you had to look big, even if you weren't. Not for him ninepenny words and five-and-sixpenny lines; he would think in terms of half-page advertisements at the very least.

Half-page advertisements and components by the thousand ... where was the money to come from? Why not write another article for Practical Wireless? The article was accepted, although it was not published until the following November - no instant cash there. But then he saw Practical Wireless advertising for an editorial assistant; he applied for the job and got it. He told his parents it was a holiday job. After a decent interval, he told them that Practical Wireless thought very highly of him and that there were tremendous prospects there - none of which was true.

|

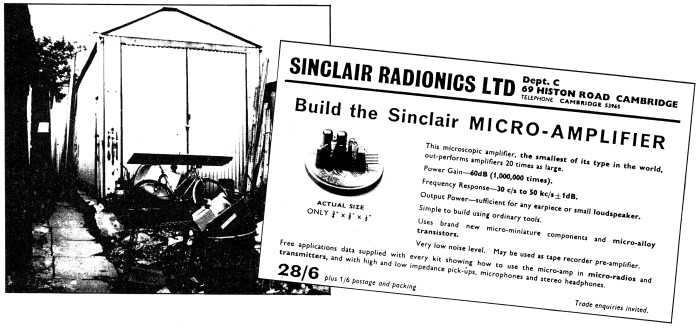

| Above : Clive Sinclair in 1978 Below left : Sinclair Radionics, 1963 Below right : The first Sinclair Radionics ad, 1962 |

|

But as it turned out there were tremendous prospects because the magazine was run by an incredibly tiny staff: editor, assistant editor, and editorial assistant - Clive. The editor had to retire through illness and the assistant editor stepped into his shoes. He soon collapsed under the strain, and there was Clive Sinclair, at the age of 18, running Practical Wireless. He says that it was not a difficult job; all he had to do was to take the material from the regular contributors, look through the articles which poured in from hopeful amateurs, select enough for a well-balanced magazine, and give them an editorial polish. The day a week that editing PW took gave him plenty of time for further reading and circuit design. PW readers could not always get his published designs to work, but a design that didn't work always resulted in a large postbag.

A job which occupies an active mind for a fraction of the time lacks satisfaction. The Silver Jubilee Radio Show opened at Earl's Court at the end of August 1958, and Sinclair was representing PW, on Stand 108, selling magazines and subscriptions, and still wondering how to launch his own business. Opposite, on Stand 126, was Bernard's Publishing.

Sinclair recalls: 'There I was on the Practical Wireless stand, when all of a sudden an immense figure loomed up. It was Bernard Babani; out of the corner of his mouth, best gangster fashion, he said; "See you at the coffee stall in ten minutes."' At the coffee stall, Babani offered Sinclair £700 a year to run his publishing company. 'Maybe,' was the murmured reply, 'but I expect a rise after a short time.'

At Bernard's, Clive Sinclair designed and sometimes built circuits, and Mr Singh did the drawings and prepared the artwork for printing the books. The secretary, Maggie, did everything else. Sinclair's mother had been dubious about her son leaving the security of a monthly magazine but Bernard Babani said to her: 'Mrs Sinclair, your son's name will be on all the books we publish.' Many a true word; 25 years later that storeroom which was Sinclair's office is stacked high with books about microcomputers - and you don't have to look hard for the name 'Sinclair' on the covers.

But his burning ambition was still to start his own business and in 1961 he had registered a company, Sinclair Radionics Ltd, on 25 July. He took his design for a miniature pocket transistor radio and spent some time seeking a backer for its production in kit form. He gave in his notice to Babani, only to find that his backer had developed cold feet.

He needed another job to earn some money - both to live and to finance the business he was determined to start. He had little difficulty in finding one; he joined United Trade Press - based at 9 Gough Square, just off Fleet Street - as technical editor of the journal Instrument Practice.

His name first appears in Instrument Practice as assistant editor in March 1962. He lost no time getting to work, and 'Transistor DC Chopper Amplifiers' appears in two parts in May and June, followed by 'Silicon Planar Transistors in Hearing Aid Design'.

His last appearance as assistant editor was in April 1963, but the year he had spent marrying UTP to the semiconductor industry was of great mutual benefit. As a journalist he could approach all the semiconductor manufacturers and was welcomed with open arms.

One of the facets of Sinclair's genius lay in his ability to reduce the size of his designs. Although he had a sound grounding in theory, he was also very practical. He knew that manufacturers were selecting components to meet their published specifications, which left them with 'rejects'. These 'rejects' would obviously meet some specification; the art was to determine what that specification was. Having done that, he could design circuits in which components would perform perfectly well. Thus did he move from publishing to marketing.

The first intimation that the world had of the existence of Sinclair Radionics Ltd was the half-page advertisement which appeared in the hobby magazines in November 1962. This was for the Sinclair Microamplifier, 'the smallest of its type in the world', which 'out-performs amplifiers twenty times as large'. There was a picture of the Microamplifier sitting on a halfcrown.

Sinclair set up his research, development and marketing organisation in his office at Gough Square. However, the address given in the advertisements for Sinclair Radionics Ltd was 69 Histon Road, Cambridge; here is some background. In 1958, I started a design and printing company called Polyhedron Services, and two years later had moved to 69 Histon Road and become involved in the development of Cambridge Consultants Ltd. CCL was founded in 1960 by Tim Eiloart, a Cambridge chemical engineer.

When CCL wanted to set up a workshop, I let them the disused bakehouse at 69 Histon Road. By this time, Tim Eiloart had met Clive Sinclair; Clive had just set up Sinclair Radionics and needed an organisation to receive his mail, assemble sets of components into kits, and despatch them. It wasn't quite the high-tech work which CCL had envisaged but no matter; as the Sinclair advertisements appeared CCL was ready with the servicing organisation.

The half page Micro-amplifier advertisement was repeated in December 1962; and in January was expanded to a full page. Not knowing what was going on, I was somewhat surprised when we were asked to print a second batch of 1000 data sheets. The idea of 'stack it high and sell it cheap' by mail order was one with which we at Cambridge Consultants and Polyhedron were unfamiliar. 'He's either going to become a millionaire or go broke' we muttered to one another as piles of mail mounted.

The next thing we knew at Polyhedron was a request for 1000 cards regretting that, owing to an unprecedented demand, there might be some delay in despatching your Sinclair Slimline. This radio, the dream on which the original Sinclair Micro-Kit Co had been built, was announced in February 1963.

Sales were going from strength to strength; ideas for products were coming thick and fast. The CCL workshop was burgeoning, and the upper floor of the bakehouse was becoming somewhat overcrowded.