| Adventure |

ONCE UPON a time in the remote era of the early 80s, adventurers knew exactly where they stood.

When they entered a software store they could ask the assistant for an adventure and be fairly sure that they would end up playing a pure text-based game of the Crowther and Woods variety. No frills, no nonsense, no pretty pictures - just a pile of deduction problems without time limits or fast-reaction sections.

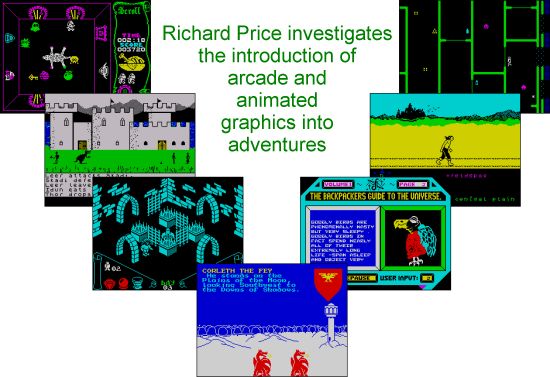

Things have changed since then. The increasing sophistication of machines, programmers and users has spelled the end of comfortable assumptions about adventure. More than anything else, the vastly improved graphics capability of home micros has turned this end of the software market into a confused blurred area.

Now there are arcade adventures and graphic adventures, in such profusion and variety that many defy easy definitions.

Early programmers were faced with a simple problem - adding pictures to a text game used up valuable RAM and drastically reduced the memory available for vocabulary. That would result in descriptions bare of any real atmosphere, badly affecting the playability and general appeal of the game.

Pleasant illustrations of the locations were all very well but players were often peeved to find that they had lost a lot of complexity in the trade-off. Purists would sneer at such unnecessary waste, feeling that companies were conceding to the demands of the contemptible arcade market.

Snobbery aside, there is a lot to be said for the adventure untainted by graphics - Artic has produced very fine and difficult games in its perennial A, B, C series whilst Level 9 has programmed some of the very best of British adventures with Lords of Time and Snowball. Their intricacy is formidable and there is very little doubt that they will remain classics of their type for a long time to come.

Nowadays the majority of commercial adventures use location graphics. Programmers have learnt a great deal about squeezing information to get the best of both worlds - or nearly. Even the most staid, conservative adventure player will not raise an eyebrow to such practices anymore.

It is the power of the arcade game which has begun to exert strong and almost irresistible pressures for change in adventuring. Whatever you feel about them, arcade games, if they are well made, can be utterly compelling, mainly due to their visual qualities. So what is the difference between text adventure and arcade game?

The skills needed for each type are distinct. In style, most arcade productions deal in your understanding and manipulation of spatial relationships. The problems tend to be of a similar type in any one game and require fast reactions and manual agility. Any sort of intellectual input is limited and the range of activities the central character can perform rarely extend beyond two or three physical actions left, right, jump, fly or the like.

Take a look at Miner Willy, or Ziggy, the odd little hero of The Backpacker's Guide to the Universe. Nobody would argue that they can do much or that they possess wildly interesting personalities. There are also no other characters to relate to - the 'other' in arcade games is usually something to be destroyed or used in some way.

In text games there is a vast difference. Whereas in the arcade you progress in a simple linear way from screen to screen, in adventure you are provided with an interlinking and mappable world for exploration as you choose. Problems are hidden or obscured in some way and your major activity is mental. The stress is on persistent thought, intuition and deductive thinking, almost always in a verbal form. The visual has played a very minor part until recently. Puzzles will vary, running from codes to wordplays. Above all, you are given far more time to resolve problems, allowing you to reflect and try an alternative strategy.

Personalities abound - through your own imagination you can become the character you want to be. Other people in the game can also behave in a rudimentary human sort of fashion and your success depends on your ability to understand them rather than your speed at killing them. So far this has simply not been a feasible proposition in arcade games.

Slowly but surely the two species are now beginning to intermingle. Finding the missing links is difficult but there are a few types of game which cry out to be candidates.

Although they may not have been hugely popular the monster mazes can claim some part in the history. In those you travelled through large three-dimensional mazes avoiding dinosaurs or vampires, all the while collecting valuable items. There is no text input of any note in those games but they clearly had an influence on today's animated adventures.

Then along came Valhalla, where the vicious and unpredictable inhabitants of the Nordic afterworld come to life before your eyes. The little stick figures walk, eat, fight and die on the screen whilst you take part in their antics in a text adventure of some complexity - players are still racking their brains to find the magical objects and there is no sign of its popularity waning. Animation had arrived with a vengeance and in a way about which traditionalists could not really complain.

The speed of development since Valhalla has been astonishing. Halls of the Things was a milestone in the use of at least some adventure themes in what was essentially an arcade setting. The labyrinthine cavern of the game has doors, treasures and a variety of swift and deadly monsters all shown in a cellular system of interlocking locations.

Magic spells and combat routines are possible and planning plays a great role in your survival. Manoeuvring and manipulating the central figure is no simple task and jaded D&D players can take time out from their cerebral fantasy by enjoying a visually exciting and mentally taxing bit of cut and thrust.

Halls really set the cat among the pigeons and the companies began falling over one another in their attempts to outprogram the other - no bad thing as there have always been plenty of goats sprinkled amongst the sheep of the industry. Knowing the public has the ability to be discriminating concentrates the mind wonderfully.

More experiments followed. The Oracle's Cave took a standard adventure plot, animated the central character's journey through a group of caverns and introduced the idea of the single key process to cover certain actions. The animation is superior to that of Valhalla though the game does not have the same area or number of possible actions.

The Cave is interesting but is not very gripping to play. All too often the strict time limit on each quest means that you rarely finish. Dorcas has improved the format and eliminated the constricting time scales in its new game The Runes of Zendos, which uses similar animation.

| 'Animation had arrived with a vengeance and in a way about which traditionalists could not complain' |

Sprite graphic techniques and the use of various types of three-dimensional image have now brought what are effectively animated cartoons within the reach of the Spectrum user. One leader in this field is Ultimate.

Atic Atac can be said to be the first in a new generation of games where adventure motifs are combined with the thrill and visual appeal of the arcade. Pseudo-3D is achieved by the scene being depicted from above. Players can choose their roles and must travel the haunted rooms of the Castle in search of the fabled ACG key. Within the rooms you will find furniture, food, objects and monsters - the very stuff of heroic adventure but all played with a joystick. That is no simple progression from screen to screen and many routes are available to you in your wanderings. The graphics are sharp, fast and smooth.

Knight Lore, by the same company, took the art a stage further. It is a strong contender for Game of 1984. The 3D effect is vastly improved and the pictures are worthy of a Disney cartoon.

You are given total directional control over the hero; objects have to be collected and returned to the steaming cauldron somewhere in the castle. That is nothing new.

What is staggering is that objects, furniture - even the masonry - can be moved and used to assist you achieving your goal. Precious objects may well be placed in highly inconvenient places and you will need plenty of the old lateral thinking skills you used in text adventure.

This is an arcade-quality game which can be called an adventure. So, it's not verbal, but it is intelligent and demanding in ways which will appeal to even the most stick-in-the-mud adventurer.

Controlling what amounts to a computer movie is a long way from Space Invaders or the original Adventure but it is the way things are moving now. Tir Na Nog from Gargoyle has the same filmic quality as Knight Lore though in a different style.

Here, deep in the mythical world of Celtic legend you send your hero through a landscape which shows convincing perspective with fore-, middle and backgrounds scrolling to help sustain the illusion. Unlike Knight Lore, there are other characters, some of whom may be hostile or helpful, but all living their own lives. Again, the game is almost entirely visual but adopts the style of adventure both in its aims and its enormous scope.

It would be difficult to talk about the new generation of adventures without mentioning Lords of Midnight and its sequel. The game is set apart from arcade games by using static location graphics and still retains features of the text adventure. Although it is governed by single key presses for choices the sheer vastness of the land gives you a convincing feel of taking part in the terrible campaign against Evil. The sense of moving slowly through the countryside is quite intense as the terrain 'grows' as you approach features.

The game has also taken on some of the qualities of strategy and wargaming. You must control the movements of large numbers of troops and vassals to forestall the assaults of the Dark.

Adventure is spreading its wings. There is a synthesis, where all available techniques are being used for the production of games which once tended to stick jealously to their own territories. The idea of separate compartments for adventure, arcade or strategy is becoming outdated.

Serious adventure players should not regard that as a threat to the games they enjoy most. There will always be text adventures just as there will always be pure arcade games. What is exciting is the sudden growth of novel concepts which will add to the repertoire of home computer entertainment.

The more variation, the better; it is healthy for the computing public who will have a wider choice and it is healthy for your imagination. After all, who really wants to be stuck in the same old repetitive rut year after year.

Making predictions is a tricky business - as one or two computer tycoons may well have realised by now - but the likelihood is that computers will stay well within the reach of Joe Public and will get smarter and faster as chip technology improves. Networking should he common soon and video techniques will be enlisted in the search for the game to beat them all. The 'interactive' video cartoon games in the arcades now may well be seen as primitive in a short while. What shape will the networked, truly interactive and fully animated - or filmed adventure take? Dream on.

At his inn on the moors landlord Gordo Greatbelly dishes out spicy mead and help for adventurers

NOW, that letter from Janga. I tell you I came near to tapping the messenger's skull with my club when I glanced through it. This miserable Prince Janga, Lord of Maru - a stinking sand-ridden hole if ever I knew one - summoned me to undertake a quest. And, wrote this snivelling fop, if I declined his necromancers would weave a curse so strong that my hair - such as it is - and teeth would drop out and my belly shrink.

Well, I am a superstitious man I knew well that Agonnar, his warlock, could achieve this threat. Where would my business be then, eh? What recommendation is a skinny, starveling, bald and gummy landlord? No, I knew I must forsake the comforts of the Ogre for the perils of the road - and at my age too.

Let us dwell on other things for the present though. The grim rites of the Priests of Artic still perplex many of you. On Espionage Island young Ian McCartney of Birmingham cannot leave the trail in the jungle. Consultations with the priesthood reveal that there is little point in wandering from the path - its whole purpose is to lead you to the boat.

I have a number of missives requesting help with the journey on the Planet of Death. I would suggest to the fair Tomlinson of Matlock that the force field can only be passed in this way - first, fire your laser three times at the field. Then hold the mirror and dance. I have been assured that this is the proper spell. She also asks if the green man is of use. My own experience is that he is best put out of the way and is potentially a serious danger.

Kathleen Burnett of Frazerburgh is equally stranded. She wishes to know whether there is any other route from the shed besides returning past the ravine. Ma'am, it is the only way. Then there is the prison - escape from here is only possible by bribery. Though it goes against the grain, corruption brings results.

John Evans of Merthyr cannot obtain information from the computer on the planet. It seems as if you should first ask for help or a hint. If that achieves nothing then examine whatever you can in the room and keep looking!

So much for that. Shirley Edge of Clwyd wishes to enter The Inferno but, whatever she does, cannot pass from the Portal into the Circles of Hell. I cannot help her here but those of you have been that way may know.

Andrew has embarked on a Classic Adventure and is labouring in vain with a vending machine. I think you must first pour oil on it to loosen its workings and then drop any coins you have. It should work well enough then.

A metal smith of Nottingham, Ralph Venables by name, cannot even begin his quest yet - he cannot pass the great snake which blocks his way. I hope he has his flute with him - he will need it. Play this flute and you will soon see the serpent sleep. There is more, though; when you see it nodding off release your bird and the snake will flee in utter panic.

Former deck-hand Neil of the Wood is landbound in the saga of Erik The Viking. Ah, Neil - this is no mystery to one such as I! If you wish to board the Gold Dragon, Erik's longship, do thus: summon your crew with a horn blast. When they have assembled at the boat-shed, pull the ship down to the shore. Here you can enter the boat at your leisure.

Simon Yates watered his steeds at the Ogre whilst returning from Kentilla. He tells me that saying 'Kentilla' transports the great sword to your hand - useful in a fight. To cross the river Cara adventurers should throw or swing a rope, and pulling the arms from a gargoyle statue within the castle will open a steel door leading to a teleport chamber. Simon could not use the furnace in the castle nor open the desk there. Should you be able to help him he can be contacted at Stoke on Trent.

So, farewell until we meet again next moon. Zul and Zel have begun packing my weapons and rations - we have ten mules for the purpose. I have little taste for foreign fare and my own beer is still the best. Tomorrow we set off for Maru. Your letters will reach me by the Royal Couriers, so fear not and keep writing.

Gordo Greatbelly, Landlord.

| If you have a tale to tell, or are in need of a helping hand, write to the Landlord of the Dancing Ogre c/o Sinclair User, London. |