| Software Report |

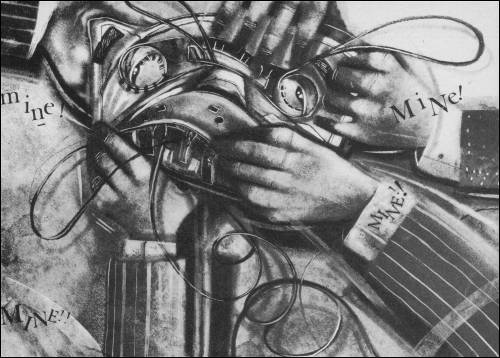

The double dealers of the software industry would fit well into a thriller plot. Sinclair User investigator Clare Edgeley reports on their shady world

YOU'VE READ the ads, you've seen the charts, now buy the game. Load it up and ... oh it's just another piece of junk software to add to the growing pile at the bottom or your wardrobe. Disappointed? Tough, you've been conned again. Still, it's only another £6.95 down the drain. Better luck next time.

If the above rings true then you are likely to be discontented with the way that software is distributed and marketed today. You are not alone; the software houses themselves are less than happy too, and some of them will not be around much longer to register that dissatisfaction.

The last eighteen months has seen a dramatic and potentially dangerous change in the software industry. At one time there was room for everyone and games of all qualities sold well. Control has now passed out of the software houses and into the hands of the distributors who, theoretically at least, are more discerning in what games they handle and are buying games in smaller quantities to avoid a glut of stock after the Christmas period.

If software companies want to get their games into multiple stores such as W H Smiths and Boots they have to go through distributors like Websters and Terry Blood, whose job it is to ensure that the games reach the maximum number of retail outlets possible.

Life was not always so complicated. Around two years ago, the bulk of games were bought through mail order where, as Andrew Hewson of Hewson Consultants states, "You put your money in the post and kept your fingers crossed for 28 days". Nowadays, games have a long and complicated journey to travel before they reach you, the end user.

Once a piece of software has been produced, the software house needs to get it into the shops as quickly as possible. In most cases an advertising campaign announces the arrival of the game and review copies are sent out to both distributors and the computer press.

The distributors attend regular fortnightly meetings with the larger stores to present the new releases. However, many software companies contact the store buyers direct, enabling them to look at a new range of games before meeting the distributors. In that way the buyers can get a rough idea of the games they wish to purchase.

Though distributors succeed in achieving phenomenal sales for some products, not everyone is happy with the way in which they go about it. Michael Howard, from the London-based Buffer Micro Shop comments, "dealers and distributors haven't been discriminating enough and second rate software has flooded the market. It has degraded the whole software scene."

The criteria used by the distributors is not purely based on the quality of the software. "I prefer to see all the games first to make sure that the standard of programming isn't slipping", says Stephanie Thompson, buyer at Boots, "I won't take on a game unless it has a minimum of three months healthy shelf life". Educational software, for instance, is a notoriously difficult product to get past the middlemen.

Various other factors affect a game's chance in the race to the shop shelf. Both buyers at W H Smiths and Boots agree that packaging is very important and that games should be presented in the most compact form. Games in large format video style boxes, such as the Level 9 adventures, are thus at a disadvantage to begin with.

Anything out of the ordinary is also difficult to market. Software house Craig Communications discovered that when it launched System 15000, a game which is all about hacking and one which could take months to break. "Many distributors were very hesitant in taking it on as it was so different and didn't fit into a specific category", says David Giles of Craig.

Fortunately, System 15000 was well received by the computer press and also had coverage in the Sun, Mirror and Daily Mail. The amount of coverage the game received helped in persuading the distributors to carry the game.

In general, the smaller, maverick, software publishers are less happy with the situation than the larger companies, such as Ultimate and Melbourne House, who are guaranteed sales and are happy to toe the distributors' line. Andrew Hewson for instance, believes, "The distributors are doing a great service to the buying public. At the moment the dealers demand a good margin to protect themselves against bad games, but I believe that their percentages will eventually drop".

Those margins - often as much as 60 percent - can, however, be crippling for small companies.

As in all cases, the middleman has to be paid. The distributors demand a huge discount when taking on a game, part of which they keep as their fee with the remainder going to the retailer.

Distributors operate on a credit system and normally pay for a game 30 days after ordering it. However, many are experiencing cash flow problems and it is rumoured that some demand as much as 60 days credit.

There is no way that many software houses can accept those terms and many have vanished from sight in the last few months. Clement Chambers from CRL believes that by next year as many as 50 percent of the software houses will have disappeared, for a variety of reasons.

Automata is a relatively small company and has recently produced the unusual Deus Ex Machina which gained unanimously excellent reviews in the computer press. Despite that, the game is getting nowhere.

Automata refuses to meet the distributors' demands for credit and request payment with order. In the past the distributors have complied with this request due to public demand for the Pi-man games. Christian Penfold is furious: "The sales of Deus are absolute rubbish - our total sales from 6 September to 26 November 1984 were 4550, including 86 through mail order".

That is largely due to distributors suffering cash flow problems and refusing to take on large quantities of the game. At the same time, Automata cannot afford to give credit on large orders as they have to pay their staff and everyone connected with the production of the game. "The distribution to independent retail outlets is non-existent", continues Christian. "We did have trouble getting into Smiths although in the end Terry Blood and Thorn EMI took small quantities".

Joe Wood from Terry Blood comments, "The game has a high unit price but the dealers get too low a profit. The margin has prevented it getting such a wide distribution amongst dealers".

Automata is adamant that small software houses such as themselves are being squeezed out of the market by large companies with financial backing, who can afford to meet the distributors' terms and are prepared to make 'colossal losses'.

Nick Alexander, from Virgin Games, believes that at the end of the day a large company will survive longer but there might not be any point in going on if there is no money to be made. "We have been arguing for a long time that distributors have too much power. This year they are demanding more margins on longer payment terms than in the past and the industry is having to give in."

Alexander is not prepared to take that lying down, and in his capacity as chairman of the Guild of Software Houses, is trying to discourage that trend. GOSH has formed the Software Sales Service which acts for Bug Byte, Quicksilva, Ariolasoft, Virgin and CBS in a planned move to cut out the middlemen.

The sales team will sell direct to the retail outlets and CBS will act as the manufacturing plant to stock and distribute the games. It is hoped that with GOSH acting separately, they will be able to take a firmer line in negotiations with the distributors.

One solution to the problem would be to appoint a small number of distributors to act for the software industry, considerably reducing their numbers which stand at present around 50. They would receive a smaller discount but would be handling more software.

On the whole, software houses, distributors and retailers all agree that good reviews can push up a game's sales whereas bad reviews can cause a lot of damage.

CRL believes that a bad review can affect sales of a game by as much as 25 percent. That is not, however, borne out in the case of War of the Worlds, where luke-warm reviews did nothing to prevent high sales of the game.

Automata, on the other hand, does not place as much reliance on reviews, though admits that good reviews can persuade distributors to handle games.

Some games with short shelf lives, such as Thor's Jack and the Beanstalk, are in and out of the charts before the damning reviews are even in print. The overnight success of such games is due to the added ingredient 'hype'.

Advertising, more than anything else, will help to sell a game. At sometime or another most of you will have bought a game which has been hyped through the advertising media. it does not necessarily follow that a heavily advertised game is going to be good. The fact remains, however, that a game that is advertised well enough will sell.

A strong advertising campaign also brings the game to the notice of both distributors and reviewers. Large software houses can afford to spend vast sums on advertising but the smaller ones cannot. Consequently a brilliant game may not sell as well as a poorly programmed game which is extensively hyped.

Geoff Brown, from the distributors Centresoft, expects games to be sent to him for evaluation prior to acceptance, although "If a game has been heavily advertised I would have to stock the game even if I didn't receive a review copy. The advertising would have created a demand and the dealers will often want to buy it."

You can only buy what you see and read about. If a game is not available in the shops it is forgotten and quickly fades from sight. Deus Ex Machina might be one such game, whereas Monty Mole from Gremlin succeeded for reasons which had little to do with the quality of the game.

According to Ian Stewart of Gremlin, Monty Mole was "a poke at Scargill" and had a lot of coverage from the press as well as being featured on News at 10. "We didn't aim to get adverse publicity, even though that can be beneficial. It was just as well the miners' strike continued or we would have fallen flat on our faces."

Criticism of hype comes from Clement Chambers of CRL, somewhat strangely considering the promotion that went into War of the Worlds: "Too much money is being spent on huge advertising campaigns and there is a lack of business sense and aggressive selling". Chambers does not believe in spending money on a lot of advertising and puts his faith in good reviews and sales promotions.

The charts are another area in which games can be hyped. There are two kinds of charts, one based on the quantity of games brought from a wholesaler and the other based on the number of games sold through shops.

However, there are occasions when a game enters the charts under false pretences. It is rumoured that in one case 800 copies of a game were sold to a dealer at half price. The dealer effectively bought 400 copies and received 400 free - the game jumped to the top of the charts.

And there are cases when genuine mistakes are made. Ghostbusters on the Spectrum entered the charts of a well known weekly magazine at number 4. That was before the game had even been released! The mistake was due to the game entering the charts at number 4 on the Commodore 64 and being placed in the same spot on the Spectrum chart.

Whatever the reasons for games reaching high chart positions, it nevertheless has a healthy affect on sales.

"Hype is useful - if you hear enough about a particular product, you will return to have a look at it in the end", says Colin Stokes of Software Projects talking about the range of budget software marketed under the name of Software Supersavers.

Producers of budget software, along with everyone else, are experiencing great difficulties getting their ranges onto the market through distributors. Stokes repeats the general view that the problem lies in the vast amount of software on the market and the fact that some distributors are wary about accepting the ranges due to the low profit margins involved.

To get round the problem Software Projects has decided to bypass the distributors and are attempting to market the range themselves by dealing directly with the dealers through a sales team. The £2.99 price has been lowered to £1.99 to compete with the Mastertronic range.

There has long been a glut of inferior software in the shops and there are few signs that this will change. At present the people least capable of judging the worth of software - the distributors and dealers - are deciding what will appear on the shelves. Of course, the software industry has to a great extent brought this upon itself in its attempts to make a fast buck with poor programs. The smaller houses are suffering the consequences.

What can you do about it? The entire industry has one objective: to make you buy software. If you stop buying games because they are just not good enough then the industry will have to change its tactics.

The next time you buy a game which does not live up its promotional blurb, complain. Write to Sinclair User and warn other readers. Write to the software house and explain why you will not be buying any more of its products.

More importantly, if you cannot find a particular game which has received favourable reviews, pester your local shop until the staff agree to order it. Contact the publishers and get them to bring pressure to bear on the distributors. Complain to the head office of the retail chain in question.

Above all, don't be content with the second rate. There is enough of it around already. Don't buy it - it only encourages them.