| Opinion |

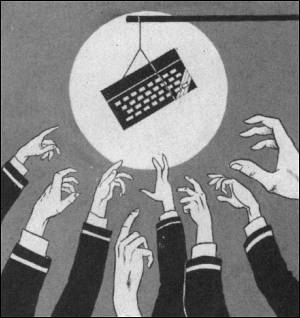

David Dodds attacks the use of school micros

JANUARY 11, 1985 was an important date in the educational calendar. It was the day when the Department of Trade offer of half-price computers to primary schools ended.

As an ardent admirer of the Sinclair Spectrum, and as a junior school teacher who believes that the computer has a real contribution to make to good educational practice, I believe the scheme has failed on two counts.

To begin with the offer has inflated the importance of the BBC micro. That has come about because cost-wise it is made to appear an offer that is 'too good to miss'.

The offer has also inflated the price of the Spectrum, for although Sinclair dropped the price of the Spectrum at the outset of the offer, that saving was never passed onto the educational purchaser. Consequently, a school pays more for a Spectrum than it needs.

Originally the Government offer of a computer for every school began with an offer to secondary schools, and it began without the inclusion of the Spectrum. At the same time as the original offer, sans Spectrum, the Government created a 'supportive agency' to be known as the Microelectronics in Education Project - MEP. From the outset that agency has been hard at work producing software for the BBC.

There is nothing wrong with the BBC from the standpoint of its use in a classroom. Indeed, its 'real' typewriter keyboard is a positive advantage. However, the cost of installing it is a different story. The BBC is expensive, even when half-priced. Added to that schools soon found that a disc drive was not a luxury, but essential.

Now comes the crunch. How does a school with 400 children give them the all important, and much trumpeted, hands-on experience?

At our school we have solved that problem by turning to the Spectrum. The economics are simple. To a school the 48K Spectrum is just over £100, microdrive and interface another £80.00 and a black and white portable television £37 - total outlay £217. Thus an entire system can be purchased for the price of a BBC disc drive!

The microcomputer is only as good as its software provision, and unfortunately the provision for the classroom micro has been lamentable. Virginia Makins coined a very apt epithet when she wrote in the Times Educational Supplement:

"Go into any big WH Smiths, and its all too plain that, even if Driller Killer has disappeared from the video libraries, Driller Skiller, the educational computer nasty, is prominent on high street shelves."

Indeed they are, and not only in the high street - unfortunately they are also in the MEP catalogue of recommended software, and, most unfortunate of all, they are in the classrooms.

How sad it is. Seymour Papert, the originator of Logo, and the great proponent of 'children and computers', was saying a decade ago: "In many schools today, the phrase 'computer-aided instruction' means making the computer teach the child. One might say the computer is being used to program the child. In my vision the child programs the computer."

When the Government scheme was first announced, two years ago, a letter was sent to every primary school from Margaret Thatcher. It makes interesting reading.

"... I hope this scheme will mean that, by the end of 1984, every primary school has its own microcomputer and will be giving young people the experience they need with the technology of their future working and daily lives ..."

And all the children have got are Driller Skillers!

In our school we have chosen a different course. What do real computers do? According to Sir Clive they word-process, manage databases, utilise spreadsheets and provide graphics.

He thinks that those applications are so central to the purpose of the computer that he gives them away free with every QL. They sound nice too: Quill, Archive, Abacus, and Easel. We, too, have chosen four areas to develop; we call them, Quill, Archive, Easel, and Lexicon.

Quill is the word-processor. Our seven year olds are introduced to word-processing through Primary Pen, from GED Software, a simple but effective program. Further up through school and our nine and ten year olds use Tasword II: I never cease to be amazed at how skilfully they use it.

Archive is the database. Projects and topics in the primary school lend themselves to database applications: births at the bird table, houses in the village, parish records, census returns, traffic surveys and so on. We use Vu-File because it is a 'creator database' - which is an empty format into which the children can construct their own fields. That is real computer-aided learning.

Easel is a drawing board. We have found that the most satisfactory way to put high quality maps, plans and illustrations onto the computer screen is to use the Digital Tracer by RD Laboratories.

Lexicon is the word-builder. Word-building for concept development, and word-building for control. For conceptual development we have Logo, and what a magnificent program it is. An exact replica of the original Papert Logo, unlike a lot of diluted fakes on the market. Logo can allow a child to control an attached turtle, and so learn about the mechanics of special geometry, and it can control an onscreen mock-turtle and so enable the child to 'teach' the computer, and to enter the world of programming in a very positive way.

All that adds up to children becoming computer literate in the real sense: knowledge of how to use the machine, and alert to its potential.

January 11 was the day when computers in the classroom came of age. Now they are on their own.