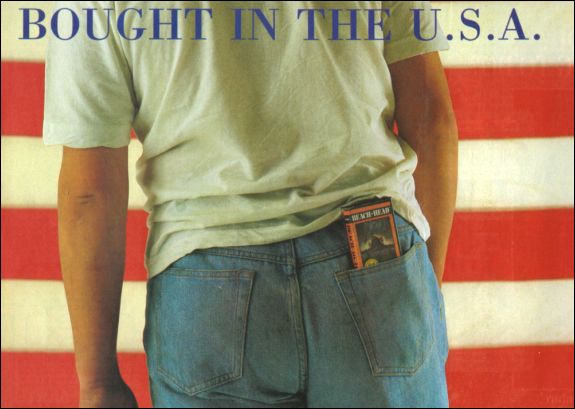

| American Sellout |

As American games invade our charts, Chris Bourne takes the crust off the apple pie and assesses the quality |

RUBBISH. Unadulterated ripoff pap for suckers with a fat wad of notes in their billfold. American software - about as nourishing as a cardboard waffle smeared with jello. As original as Dynasty, as talented as Madonna, as intelligent as Rambo. And by God's own country, doesn't it sell well in the UK?

The truth is, you can expect to see at least five American games in the top 30 every month - and that's likely to rise come Christmas. We've always been proud in the UK of the quality of our software, and that includes business and mainframe programming as well as the games market. But is it really as good as we think? Is the stuff brought over from the Americas better? And if it's the rubbish most British software houses like to think it is, why does it sell so well?

In other words, are you, the games-buying public, tasteless wallies? Or is the hype taking you for a ride? or and a thousand programmers shudder in fear at the thought - have the Yanks got something we haven't, and really do give the public what they want?

Stay tuned for the facts, and judge for yourselves ...

Some people would have you believe there's no such thing as a software industry. "It's just a lot of people who don't know each other," says David Ward, a major shareholder in us Gold, the leading UK software house dealing in American games, and the leading software house in sales, period. Yes - nobody flogs more plastic into the distributors than US Gold. That's the reality of the market.

Ward resists the idea that there's any real difference between the American and British industries, because he rejects the idea that you can define what the industry is nationwide. So why is US Gold software advertised as 'All-American software'? Buy this, it's from the Big Boys - that's the message, and to judge from the sales, we lap it up.

"There's no reason why it should be any different from anything else," says Ward. "Thirty per cent of TV shows are American. That's what's in the ratings. It's the same with anything."

Maybe that's why his own company, Ocean, is bringing out Rambo - Fast Load Part II. Hey, do you think they'll have the bit where he blows the gook apart with the exploding arrow? Wouldn't that be great?

Well. The American software industry, if it exists, is certainly different. The games we see over here are not necessarily the hits from the States. Ariolasoft's strategy game, Archon, bombed in the UK, but was plugged on the packaging as a 'US Top Ten hit'. It's a sluggish strategy game, a sort of chess variant with magic and arcade sequences for deciding who takes what. It never stood a chance over here, and you won't see US Gold bringing anything remotely like that across the herring pond.

"According to the Billboard charts, simulations seem to be really hot." That's Dave Gardener talking, project manager for Electronic Arts in California. Simulations? You, try getting a simulation-to number one in the UK charts. The last time it happened was with Chequered Flag two years ago. What about the arcade games?

"Arcade games haven't been able to maintain their position. Look, we shoot for a shelf life of years." It's true. Flight Simulation, a granddaddy of the genre from Microsoft, has been topping the charts on and off for the last three or four years.

Today's big American games are massive disk-based productions. They cost around $40 - even cassette games cost at least $20 over there. At the upper end of the market, the games cost more than the cheapest computers.

They're complex games, full of detail. Gardener cites Spanish Conquest as an example, where you sail from Spain to conquer the New World. "What's been put on it is 11 million square miles of playing area with 2,800 different screens. That takes up an entire Commodore disk and it never stops running."

It sounds great, but it also sounds a bit daunting to those of us who call 60 screens 'massive' and can easily get lost in a tiny fraction of the playing area. Why do they think so big out there? Is it part and parcel of being American, working in skyscrapers and owning Cadillacs? Does it just go with the territory?

"The people buying our product are older," says Gardener. "People I talk to say 'No! I don't wanna buy a game! Music - that's cool. I want into that.' You can bring out a pinball game like a construction set - people can change it and just get a kick out of that. The products that sell well are simulations, and incredibly detailed."

Along with Spanish Conquest, here are a few of the games you won't be seeing on the Spectrum - this Christmas or any other. Alternate Reality - that's a role-playing adventure game by Datasoft, who produced the more familiar Bruce Lee. It has brilliant 3D graphics and comes on seven disks as a series. The whole lot would set you back $240. Or there's Activision's Countdown to Shutdown, with its 2000 room energy plant 'the size of a small city'.

Not everybody likes the way the US market is going. Rick Banks of Sydney in Ottawa, which produced BC's Quest for Tyres and Dam Busters, for one. "Software is ridiculously expensive here", he says. "I almost feel guilty when I walk into a shop and see games selling for $40. It's not fair. The kids are being ripped off."

OK Rick, so why not sell them cheaper? Mastertronic, our own budget software house, sells games in the States for $10. That's dirt cheap. "It's not from the development side of the industry. But if we went for British prices then it would be difficult just to break even."

Banks talks about games as games, not 'computer entertainment' which is the standard phrase used in the States. "They talk about computer games as art," he says. "I'm not embarrassed by the fact that they're games. In North America they get carried away with options and construction kits. If there's a byte you can change, it turns into another option."

Dave Gardener backs that up. "I shudder to call them games," he admits. He's proud of the complexity of a total computer entertainment environment.

"Maybe the English just want to get in there and have fun," he says, sounding perhaps a little dubious about the idea.

"You know, gameplay has got something to do with it," says Rick Banks. "Having fun."

That's what they're playing in the States, and it sounds a lot different from the sort of programs sold by US Gold, or Activision. Those games are completely arcade-orientated, often taken from coin operated machines, converted to the Commodore 64 in the US and then to the Spectrum in the UK.

American software houses don't write for the Spectrum at all. Most don't understand it, and if they do they tend to look down on it. In the USA Sinclair means the ZX-81, and forget it. They certainly boggle at the prices we sell games at. Even cassettes usually cost $20 at least.

It took two years for US Gold to persuade American software houses to sell games over here, through them. But the attractions to UK software houses of licensing American product were enormous. Geoff Heath used to run Activision UK, which handled Ghostbusters, so he should know a thing or two.

He says the attraction to UK software houses of licensing American games is because you get instant games. There was a backlog of titles built up, programmed for the Commodore 64, which could be instantly released in the UK, followed a couple of months later by the Spectrum conversion.

"Not just the good ones," adds Heath. "The bad ones came over too." He freely admits - now that he's working for Melbourne House - that Ghostbusters, the leading Activision game, was never much good on the Spectrum. Ghostbusters sold on the back of the film. Activision claims to have sold in excess of 300,000 copies, a staggering total when you consider that 50,000 makes a game a big hit in the UK.

"Mind you," says Heath, "They're not all bad. I tried to get Beach-head - I thought that was terrific."

Ghostbusters was written in the US by Activision's David Crane. Crane also wrote the two Pitfall games, and he's something of a star in the States. He earns large quantities of money, "somewhere on the level of a corporate vice-president," he claims. But the games, converted to the Spectrum, look tatty and old-fashioned.

That's probably because a lot of US software over here is old-fashioned. It's the backlist of games, built up over the years, now picked apart by UK houses. Rick Banks says Dam Busters, only just released by US Gold, was originally written three years ago. That's one of the good ones. BC's Quest for Tyres, due out soon from Software Projects, is four years old.

Four years ago our games industry was pathetic compared to those programs. Today, programs like Dun Darach and Way of the Exploding Fist knock spots off most American games available for the Spectrum.

"The games are simply too large to be converted," says Heath, "and the market is smaller than people think. The number one company over there is Infocom - producing text-based adventures. Beach-head was not relatively successful in the States."

Adventures do cross over, and fairly successfully. Adventure International UK was set up by Mike Woodroffe to handle the growing demand he found in his shop for the games. The sister company in the States is the home of Scott Adams, who first brought text adventures to home computers.

Although those games are all disk-based, and supposedly far too long for the Spectrum, Woodroffe and his colleague Brian Howarth, who wrote the Mysterious Adventure series, have few problems squeezing them down to size for a single load cassette. That's partly because we're not used to the quality of graphics on American adventures, which load in a whole screen off the disk, but also because if you're writing for disk there's little need to be efficient.

"If you've got a lot of memory available you do tend to write sloppily," says Woodroffe. "Some of Scott's games take up much less space the way we do it."

Mind you, Woodroffe is making concessions to the extreme old age of the original Scott Adams games - he's bringing them out in twin-packs, two at a time. "We didn't think we could fairly charge the full price for a single game, given their age," he says.

The new series, Questprobe, based on Marvel comic characters, is a different kettle of fish. Those are coming out reasonably quickly after their launch in the States, but they don't really match the high quality of the Infocom adventures such as the Zork Trilogy, or Planetfall. Those are highly literate games, with upwards of 800 locations per disk. Adams' games, once the best in the world, are much more downmarket productions.

So there are a few points to bear in mind when you feel tempted to buy American. Firstly, the best games will never get onto a Spectrum mainly because they are far too big to get onto a cassette.

Secondly, what you get offered in the shops is often old, out of date stuff. Just because it was once a hit in the States doesn't mean you're going to like it. You can't always trust the screen shots on the cassette, either - SEGA insists that US Gold use Commodore or coin-op shots even on its Spectrum games.

Thirdly, there's no guarantee that it's going to be good because it's American. Some of it is, some of it isn't - but it was written for a different market to start with, and tastes change.

David Ward is satisfied that the games stand or fall on the verdict of the consumers. "You can't kid the kids," he says. "What the public are offered and buy is what they think is the best."

Is it? Ghostbusters wasn't. Why did you buy it?

A lot of British software houses resent the lead US Gold has in the UK market. Part of that is sour grapes, but none of those games, or any other import from America, is as good as the best of our software.

But if US Gold is dethroned, it will probably be because the supply of good games which can be converted dries up, rather than through our own programmers beating it into the ground on sheer quality. David Ward doesn't think that will happen. "Current releases are as many and varied as ever," he claims. "If you assume they're available for licence there'll be as much around."

It's downright impossible to reconcile that with Geoff Heath's view. "All the existing product is used up," he says, unambiguously. "People were able to release an accumulation of product in six to nine months. Now that's over, the amount of product available is a lot less."

And the new stuff, the good stuff, is the mega-games, the giant disk operas, the zillion screen experience. If those make it to the UK, they will make it on the Atari 520ST, the Amiga, and other machines with built-in disk drives. If those machines take off, the games will follow - "Simple hot and deep," as Dave Gardener puts it. "Space Invaders is not deep," he says. "We wouldn't have that in the US. Products in the US have to be deep."

"Oh, we would like to see that very much," says David Ward. "The UK market was built on cheap disposable software at pocket money prices. It depends on whether people build a home computer environment. If they do, we'll certainly be in there."

You can bet your forty buck diskette he will.