| User of the Month |

Does Manic Miner improve your cognitive development?

Joe Palca finds out

CONTRARY to what you may have heard, computer games are not a waste of time. That at least is the opinion of Dr Michael Anderson, a researcher at the MRC Cognitive Development Unit in London. He believes that computer games require new types of thinking. Moreover, he sees them as a potential learning tool, one which may open doors for children who cannot be reached by more conventional educational techniques.

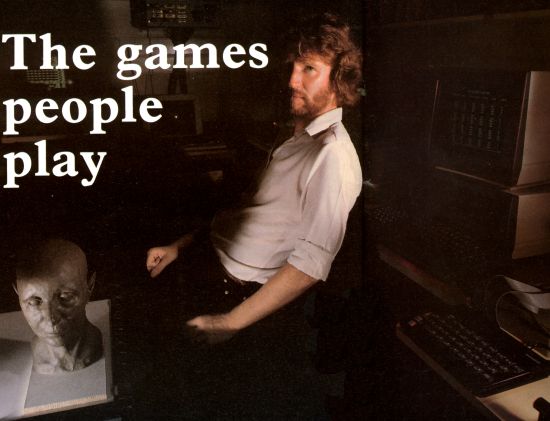

Anderson certainly does not fit the stereotype of the stuffy academic. He has a full red beard to go with his somewhat shaggy red hair and, in place of a white laboratory coat, he wears a button-down shirt and jeans. His broad Scots accent immediately indicates he does not hail from London.

Some of his ideas set him apart from the majority of educators and academics. He believes that people underestimate how much thinking is required to play a computer game successfully.

"Computer games may look just like fun, but there is an important amount of real learning which goes on in them," Anderson says. "What I am interested in is the kind of learning that is possible within that framework."

Anderson is trying to study what goes through a game player's mind during a game - what a psychologist would call the cognitive strategies a player uses. He has begun experimenting with how people learn to become good at computer games.

"We are using the Spectrum for two main reasons. One is that we are interested in the computer game format to investigate cognitive development. The thing about the Spectrum is that there is plenty of software available for it. As anybody who knows anything about computers finds, writing games software is tricky.

"The second reason is that we will probably be taking our equipment into schools. The Spectrum is small and portable but it is also powerful."

Anderson began his career in psychology at Edinburgh, studying intelligence. "I was interested in individual differences in intelligence - why somebody is cleverer than somebody else," he says.

For his graduate degree Anderson moved to Oxford where he became interested in learning. There he met his first computer, a Digital Equipment PDP/BE, and wrote his first program for that machine, a simple paddle and ball game.

At Oxford, Anderson became interested in an area of psychology known as perceptual motor learning. At the simplest level, it is a type of learning a baby does as it starts to reach out and touch things in the world around it. On a more complex level, perceptual motor learning is required by a surgeon, who must learn to move his arm extremely accurately while holding a scalpel, or by a footballer who moves his body into position to head a centre into the goal.

Even a seemingly simple task like answering the telephone requires a good deal of perceptual motor learning. If you do not believe that, try writing a computer program which will be able to detect the ring, see the telephone on a desk, and then guide an arm to pick up the receiver. Despite that complexity, that type of learning has been somewhat ignored by psychologists.

"I started looking at how people improved at perceptual motor tasks - how did they improve with practice?" Anderson says. "I found there is a larger cognitive component than had been thought previously. In other words, people improve at those types of tasks because they change what they do, rather than become more efficient at what they always had been doing.

"Perceptual motor learning has never been thought of as having anything much to do with intelligence. Conventional wisdom may hold that you do not have to be very bright to be a good footballer but I do not think that is true."

Anderson is a soccer player, a mid-fielder in a six-a-side team, and recently he went to Mont St Michel for a tournament. "I suppose football is my other great obsession in life."

In his office hangs an autographed picture of Kenny Dalglish. "He's my hero," declares Anderson, "though he is getting a bit old."

Next door to his office, a small room contains the computers Anderson uses. Besides the Spectrum there is a Microtek VUB, a terminal connected to the university mainframe, and three Sirius computers, the newest of which contains a 10MB hard disc. To begin his research projects, Anderson is using a standard Spectrum, with a cassette drive for program loading. He uses an Atari joystick with an AGF interface. The interface permits him to standardise the way the games are controlled.

Sitting in front of the Spectrum, Anderson begins to load Manic Miner so that he can demonstrate some of the concepts he is studying. The joystick is bolted to the table on which the computer stands, giving him a sturdy base from which to work.

The Central Cavern appears on the screen. "The first time you see the ledges, they look solid, and you think you cannot jump through them but, of course, sometimes you can. You do not try certain strategies because you know things about the world you assume are true for the game. The game compels you to develop alternate ways of dealing with problems. When you start you bring world knowledge to bear on Manic Miner. Later, you bring Manic Miner knowledge to Manic Miner."

Anderson works his way quickly through the first few screens. "The Cold Room is dead easy. I suspect they put an easy screen near the start to keep you going," he says.

By the time he reaches Eugene's Lair, Anderson is concentrating harder on the game. "The thing about Manic Miner is that there is more than one solution. My boss spent ages on this screen. He finally found all the keys and then Eugene came down to block the exit. It was a crushing blow for him. He got it, though, and now spends his time finding more interesting ways of getting through."

Arriving at the Wacky Amoebatrons, Anderson explains that patience is an important element in the game. "Like the Processing Plant, you have to wait for your chances. I tend to panic."

At the Attack of the Mutant Telephones, idle chatter ceases. "This is as far as I've got ... this is murder ... it collapses ... I forget ... Oh, noooo." He's not going any further on this day.

Although his research project is just starting, Anderson has already had a chance to sample a fair number of the most popular Sinclair games. For the time being, however, his favorite is Manic Miner.

Anderson is hoping to turn the addictive nature of the games to an advantage. "For a large proportion of the population, especially children, computer games are highly motivating. Children like to play them. School, on the other hand, does not generate the same enthusiasm. We are trying to produce educational software which will contain some of the motivational aspects of the computer games so that children like to learn."

Anderson's primary goal is to understand the types of skills different computer games require. Before he tries to develop games to promote learning or encourage participation, he wants to know more about how much of those qualities exist in available games.

"I am planning to look at a number of games to try to find what features are important for such variables as interest, excitement; boredom, frustration and so on. I am trying to distill some of the motivational properties of the games."

Anderson plans to use all types of people in his initial experiments. "We shall run the initial studies not only on normal people and children of various ages but also on special groups - children with Down's syndrome, autistics, and so on, to see how they classify the games."

Part of the function of the MRC cognitive development unit is to provide microprocessor-based aids for the handicapped, in particular learning aids.

"If you are so paralysed that all you can do is move your eyes, you may have a perfectly well-functioning brain, but because you have so little control over your environment you may never be able to express that. When you can hook eye movements to a computer system, eye movements suddenly become very powerful. The computer becomes an interface to the world," he says.

With Warwick Smith, the unit hardware specialist, Anderson has already helped design a computer game which can be controlled by tensing a muscle. Input from the electrical activities in the muscles is fed through an A/D converter into a microprocessor and the muscle signals control the position of the cursor moving through a maze. The system is being used by a physical therapist to encourage injured or disabled children to exercise muscles which would atrophy if they are not used.

Ultimately, Anderson expects to move away from the Sinclair for his experiments, switching to his own system. His plan is to put the games software into a ROM chip and have another on-board ROM for storing the responses his subjects will make. That information will be dumped into a Sirius microcomputer for analysis.

For now, the Spectrum and Manic Miner are occupying much of his time. After all, he still has eight more screens to figure out.

|

It takes a long time to take subjects into the laboratory to study them, so Anderson is looking to Sinclair users for some help. If you are an 'expert' games player, or even if you play only from time to time, he would like to hear from you. If you send him a postcard, he will send you a stamped return envelope and a questionnaire. The results of the questionnaire will be used to classify some of the more popular computer games into the categories Anderson is planning to study. Write to Michael Anderson, London. |