| QL File |

John Gilbert draws on his extensive hands-on experience to answer the basic questions surrounding the new Sinclair machine

THE SINCLAIR QL has finally landed in the Sinclair User offices so that we can offer one of the first reviews on the machine. Despite the external EPROM containing part of the operating system which hung out of the back and bounced round when the keyboard was used, and the almost non-existent manual, the machine was up to the standard which is going to customers.

It arrives in a box three times the size of the Spectrum which contains the manual, external EPROM and free RS232 lead.

Although the machine is not particularly attractive, the keyboard works better than it looks, even if the keys, especially the space bar, had an irritating clacking sound when pressed.

When first powered-up the computer will ask the user to press either function key one - Fl - if using a monitor, or F2 for an ordinary UHF television set.

There are five function keys which can be utilised in either SuperBasic or machine code for complex tasks performed by the user. For instance, it is possible to call several procedures into operation, such as clearing all areas of the screen at once, by pressing one of the function keys.

Unfortunately new computer users may have some difficulty getting to grips with entering programs because the television screen display is different and less easily understandable than that of a monitor.

On the monitor the QL initially splits the screen into two windows, or pages, one white and one red. The white is used for program listing and the red for the results of a program, such as graphics or input.

The monitor display separates those windows but the television superimposes one on top of the other, the white listing window being the primary one.

As the windows act as two separate screens, you need two separate instructions to CLS them. The CLS 2 clears the listing screen and CLS clears the program results window. Every time the QL finishes a program you will have to perform a CLS 2 to put the listing on to the screen. It would have been better for the QL to switch back automatically to the listing window when a program has finished and list the SuperBasic code.

The size of the characters displayed on a screen differs on the television display and the monitor display. The resolution of the monitor is set at 80 characters per line but is coarser on the television setting, It is, however, possible to get 80 columns on the television set using the MODE command which will define the resolution in which the screen is displayed. Sinclair seems to have overcome its difficulties with colour displays on television sets and 80 columns is just about readable.

The program editor will alter and add to your lines of SuperBasic program in much the same way as the Spectrum, with one important difference. If you type in a line which has an error the computer will tell you about the error and promptly forget the line. You will have to re-type the line with corrections.

If you want to edit a line which you have already entered on the listing screen you must type EDIT, followed by the line number. The only reason you might want to do that is if you want to alter a line which contains an error other than syntax.

Error-checking, using the program editor, may be almost non-existent, but Sinclair seems to have learned by its mistakes with the Spectrum so far as error-checking and correcting while a program is running is concerned.

Apart from the SuperBasic commands which trap errors, the machine will also allow you to use any variable, numeric or character, without first defining it. If you ask for the contents of an undefined variable, the QL will put an asterisk into it. Error-trapping is essential on a machine like the QL and Sinclair seems at least to have that correct.

The way in which SuperBasic and QDOS are implemented with the 16-bit M68008 is an incredible bodge which makes the machine less expensive to manufacture than if it had the full power of the 68000.

The chip has an internal structure of 32 bits but the slow speed at which the QL runs shows that something drastic has been done to the microprocessor. When you look at the specifications everything seems rosy until you learn that the machine supports only an 8-bit databus.

As a result of the chip mutation, and after running several benchtests on the BBC Micro, Commodore 64 and Spectrum, it was found that the QL was slower than all those machines, including the Spectrum, if you type in a benchtest of only a few lines.

If, however, you type in a long program you will find that the computer does not react any more slowly but that its competitors, such as the BBC, do. It runs at about the same speed while interpreting long and short listings.

Multi-tasking, especially when used in connection with SuperBasic, is a mis-applied term. What you can do in SuperBasic is to run a program while at the same time accessing a peripheral such as a Microdrive to load or save data.

It is not possible to run two or more SuperBasic programs at the same time on the QL and so you cannot have Basic multi-tasking. It is, however, possible to run several machine code routines concurrently.

Despite disappointments with multitasking, the graphics created using SuperBasic can be spectacular and are as fast, if not faster, than those of the BBC micro.

There are two circle commands on the machine, one called ELLIPSE and the other CIRCLE. The latter seems to have been left in by mistake, as it is part of the pre-production operating system and does the same thing as ELLIPSE.

The ELLIPSE command is similar to that of the Spectrum CIRCLE. It allows the user to produce arcs, circles and even lines. There is also a LINE command which uses absolute co-ordinates on the screen, unlike the Spectrum, which uses relative plotting.

QL graphics are easier to use than those of the Spectrum, because each pixel can be referred to absolutely. You do not have to re-set the plot position every time you start a new line as you do with the Spectrum.

Turtle graphics seem to have been an afterthought on the part of Sinclair. Unfortunately, they seem to have been hastily implemented and, on our machine, we were not always sure that they would work in the way we intended.

The QL starts on the wrong foot by having the turtle pen up, in the non-draw mode, when initialised. To draw a line you have to type PENDOWN and even then the QL will show no sign that the turtle is in operation.

Unfortunately, the Microdrives are not up to their best with MERGE. The only Microdrive instruction which provokes anything like the response rate promised by Sinclair is the DIRectory, formerly the CATalogue, command where the names of the files on the 100K Microdrive cartridges are displayed. The Microdrive takes approximately three seconds to display the contents of a cartridge.

The access time for Microdrives on the QL is disastrous for the businessman. Quill, for instance, takes two minutes to load. They are, therefore, only slightly faster than a cassette recorder using the baud rate of a Spectrum to load a 48K program.

The response rate of Microdrives under the QL QDOS operating system may be slow but it becomes even slower when you enter the operating systems of one of the Psion software packages. Files can take so long to load into the programs that you might wonder whether the machine has crashed in desperation.

Microdrives are hopelessly inadequate for the business community and, because of the temperamental nature of operation, could pose a serious risk to data stored on cartridge. It is all very well for Sinclair to suggest that you make back-up copies of all your files, as irretrievable errors can be made during the back-up procedure with your only copy of data in the drive.

The serial interfaces on the QL are also hopeless for the intended Sinclair business market. Apart from the RS232 being slow, the business community does not regard it as standard, favouring Centronics instead, and so for business users the choice is, at the moment, whether to buy a QL in the hope of getting a Centronics interface or not to buy a QL at all.

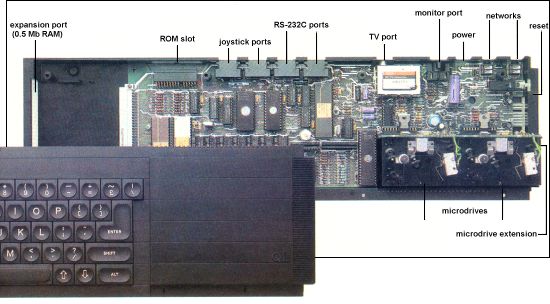

Despite the inadequate or non-existent nature of the QL peripherals, the main PCB of the machine is attractive and well put together. The hardware designers should be complimented on the compromises they have taken to make the machine operational. When the external EPROM is taken on board and it becomes possible to use 16K ROMs in the ROM socket, the finished machine will be a serious contender against the PCs and Apricots at the upper end of the market.

It is inadvisable for every businessman to order one but Sinclair should aim the machine at the serious home user and student. For the business user the machine seems inadequate and slow by most 16-bit computer standards. It costs, however, only £399 and represents a considerable achievement for Sinclair Research.

The company may have exaggerated the brilliance of the machine and mismanaged the marketing yet again, but it nevertheless has a winner on its hands. It has also broken through to the serious, upper end of the market. So long as it receives the software support the new Sinclair baby should make almost as big an impression as the Spectrum.