| Education |

Theo Wood talks to teachers about the potential of computers in education and finds the possibilities fascinating

THIS is likely to be the year when the educational uses of the computer move to the forefront of discussions among teachers in schools, both primary and secondary. One development to note is the way teachers have taken different routes to become adept at using a computer in the classroom. Some may have attended courses provided by their local education authorities, while others, having bought micros for home use, have taken them into schools and been surprised by the overwhelming popularity of the micro in their own teaching situations.

Steve Wright, who teaches at Langdon School, a comprehensive in the London Borough of Newham, already had a great deal of computing experience before he began using a Spectrum in the mathematics department. While working for his physics degree he used a mainframe and during post-graduate work was writing programs in Fortran. Buying a ZX-81 rekindled his interest in programming and he started writing programs he could use in school work. When he bought a Spectrum the process continued and there are now three Spectrums in his department.

| 'A micro has a special effect on children' |

Ken Heaton, a teacher at Gateway Junior School, Lisson Grove, London had used computers in his mathematics and statistics course at Kent University but it was buying a Spectrum which spurred him to become involved in using computers in the educational field. He first took his Spectrum for children to use in a lunch-time computer club. The response was overwhelming.

"The demand was so great that we had in the end to limit the numbers to the higher end of the school, because so many children were interested," he says.

Terry O'Brien, a teacher at Comber Grove Primary School, Camberwell, became enthusiastic about the potential of computers in schools when he attended a two-day introductory course at the MEP centre in Croydon. After that he bought a Spectrum for home use and then started to use it at school, where there are now four Spectrums as well as one RML 480-Z.

Having introduced computers into schools, the most important consideration is how their use is to be implemented in everyday learning. I spoke to Ian White, an advisory teacher for secondary education at the Inner London Educational Computing Centre. He sees the role of the computer as important in a number of areas.

"It has a very wide-ranging role. In my subject area you have the computer studies course which is taken to examination level, and that is a specialist study in computers. That in the past has tended to be the only computer education and has necessarily had to do computer awareness.

"There is the awareness of society in general and computers as part of that society has to be taught within that. Computers are used in particular subject areas to enhance those subjects."

Wright sees the computer as particularly useful in the latter field, where cross-fertilisation of work between the computer and other more conventional modes of studying is increasing motivation by the use of computer modelling and more learner-orientated discovery.

He is interested in the role which strategy games can play in the curriculum and has been using Corn Cropper, a Spectrum program, with his second- and third-year pupils to great effect.

As a teacher at junior school level, Heaton summed up his view of the role a computer can play. "I think in an infant and primary school it is important to grow with the times, so that children are used to a computer from the age off four or five, so that once they go to secondary school, it is not a complete shock to them."

For O'Brien, a computer has its place in the activity classroom, not only to help with basic skills but to introduce children to new areas of learning, such as Logo.

"A micro has a special effect on children as it is completely non-judgmental and allows them to acquire and reinforce basic skills in an efficient and enjoyable way".

Authorities vary as to which hardware to support in their schools. The Inner London Education Authority, for example, like many others, decided to standardise on the RML machines at primary and secondary level. There are obvious reasons for standardisation, as support systems can develop software and maintenance for all machines in the schools. Other authorities, such as Grampian Regional Council, chose to support the Spectrum at primary level.

Of 285 primary schools, more than 240 have ordered or have received their Spectrum kits under the Department of Trade and Industry scheme. Gavin Bell, director of the project at the teachers' resources centre in Aberdeen, says:

"We are conducting a survey on computers owned by schools but there are already clear signs that schools are buying more computers - several have four or five. One of the reasons for choosing the Spectrum was that, while the first computer is subsidised, second and subsequent machines are not. With bulk discounts our schools can buy a complete 48K kit, with printer, Microdrive and colour display for less than £400. In-service training is being carried out in stages and there is further support for teachers via regional working parties which are reviewing available software, producing guidelines on the best use of various packages, and drawing up specifications for educational programs."

The relative merits of various pieces of hardware from a technician's point of view is best argued in other forums; teachers are more likely to be interested in what a computer can do in their own subject areas. Just as there are different decisions as to hardware, it would be very surprising if there was complete agreement about the merits of various approaches in software. The child-centred approach obviously favours programs which allow children to investigate, discover and create. At the other end the teacher-centred approach would prefer programs which have a clearly identifiable purpose within the scope of skills training.

| 'The real power of computing will be seen in simulations' |

Those are the two extremes of the axis and the two views are not mutually exclusive, in that an open-ended program such as Logo can be teacher-directed, and some programs which reinforce basic skills by requiring text entry can be of the exploratory type. Teachers and parents will choose software from what is available, according to their proclivities for a certain approach, as well as recommendations from other teachers and teachers' centres. Some may even write their own programs as Wright, Heaton and O'Brien have done.

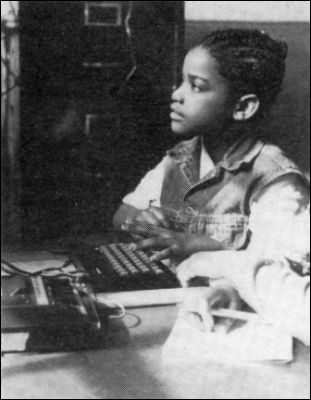

Concentration at Comber Grove |

There is a need to evaluate software beyond the review stage to discover if a particular program achieves results for a period, say six months. With his headmaster Michael Kent, O'Brien hopes to raise money so that every classroom in his school is provided with a Spectrum and eventually hopes that the school will become a centre for the evaluation of programs used on an everyday basis.

Commercial software has improved in the last year, he thinks: "A year and a half ago the experts were correct in saying they were rubbish but I think that is changing".

In the last year vast numbers of programs have been published for the Spectrum but there are still gaps, particularly in the number of information retrieval database packages, a proper implementation of Logo, and a junior word processing package. There could be many more strategy/adventure games which complement course work in various subject areas for children who have acquired basic skills.

The Sinclair Education Exhibition held in March indicated that those gaps are about to be filled. The Sinclair Logo was on show, with intended release in about a month, and a half-finished junior word processor called Scribe, written by CSH Ltd of Cambridge, was also on the Sinclair stand.

I asked David Park, Sinclair educational representative, what software developments he would like to see in the future. "I am keen to see programs which develop logical thinking and those which employ the strengths of the computer in data handling. We would hate to see a number of drill and practice programs; they have their uses but that is not the way forward. The real power of computing will be seen in simulations, something children cannot experience in their local environment, such as simulations of real events, like running a coal mine or an oil field".

The most impressive feature of the show was the control applications for the Spectrum. Griffin and George, supplier to schools was showing its interface which provides three types of inputs and three outputs. Applications on show included a Fischer-Technic model with full moving gears, a robotic arm and a panda crossing. Griffin and George supplies all the accessories, such as stepper motors and sensors to measure temperature, pressure, magnetic fields and movement.

Richard Bignall from the MEP project for the Chiltern area spoke of future developments for the Spectrum: "The developments in which we are involved are using Logo for control applications in the primary school, so that instead of just doing Turtle graphics for driving a turtle on the floor, you can plug in other pieces of hardware.

"We are hoping to produce in the next year a self-contained board for primary schools which will allow them to interface with the real world and to demonstrate certain principles, such as digital and analogue input/output. It will be expandable.

"We have been using versions of Basic in secondary schools for control applications and are working on a version of control Basic for the Spectrum.

"Looking at Logo, we hope to do the same thing in a much more friendly fashion; in fact, we are very tempted to say let us use Logo for most applications. We are aiming for an A4-sized board costing around £100, not in a box, as we want the children to see the circuits and get away from the black box image.

"The board will run two motors with reversing of the Lego type. There are plenty of remote-controlled children's toys on the end of a piece of wire which range from the talking dog to such things as racing cars, as well as model trains."

With all those developments, it looks as if the role of the Spectrum as an education machine is assured. Interfacing projects will soon be within the scope of children and adults who may have had no previous experience of electronics and, apart from the benefits to technical education, the developments look like being enjoyable and, above all, entertaining.