| Hit Squad |

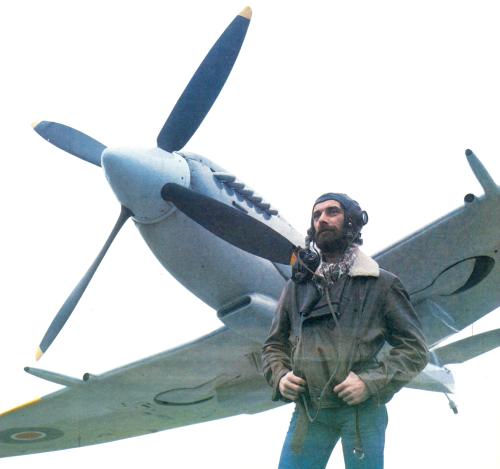

Nicole Segre zooms in on flight programmer Gibson

LESS THAN two years ago, John Gibson was living on a remote mountainside in Wales and making a precarious living by installing suspended ceilings. Today he is a mainstay of the Imagine Software team of programmers in Liverpool, author of three best-selling games for the Spectrum, and the proud owner of a metallic brown Porsche 924. "I can't believe my luck," he says, "especially at my age."

At 36, Gibson is the oldest of the Imagine Software team, whose average age is somewhere around 19. Age, however, has not prevented any of his games figuring in the charts within a short time of their release.

The first was Molar Maul, which was set, of all places, in a mouth where evil bacteria such as the green meanies and the DKs must be warded-off by means of weapons like toothbrush and toothpaste. "It sold well in spite of being in rather poor taste," says Gibson. His next game, Zzoom, was more in the classic mould of arcade games, except that it had a scrolling screen, then a novel feature, and that the enemy craft to be shot from the sky headed straight towards the player.

Gibson's present hit is Stonkers, a complex strategic war game which makes a complete break from previous Imagine Software games. Stonkers features a battle zone - "nowhere in particular but it resembles the northern coast of Europe," says Gibson - complete with marshland, river, mountains and open country.

| 'Stonkers represents a considerable programming feat, which is all the more surprising because Gibson entered the field comparatively recently via a roundabout route' |

The player's army is ranged against that of the computer and must try to over-run its supply point and military HQ to win the war. The ordinary screen display shows the battle terrain, with panels at the sides and bottom keeping the player informed constantly as to the relative strength of the two armies and individual units. At regular intervals, ticker tape messages run across the bottom of the map with the latest battle updates.

The truly original feature of the game is the way in which pressing the fire button permits the player to zoom in on any particular segment of the map, which is then displayed in fine detail, complete with whatever artillery units, tanks or supply ships happen to be in it.

Within the limits imposed by the Spectrum memory, the game also incorporates artificial intelligence techniques, with the computer making rational decisions based on the player's moves. "A fair degree of strategic planning is needed all the way through," says Gibson.

Stonkers represents a considerable programming feat, which is all the more surprising because Gibson entered the field comparatively recently and via a roundabout route. Born and raised at Mitcham, South London, he studied polymer engineering at Manchester University and then applied for a post as a trainee computer programmer with a multi-national plastics company. A promising career was nipped in the bud, however, when the company decided to cancel the scheme four weeks before Gibson was due to start, sending him on his way with a month's salary.

Gibson drove a wholesale chemist's van for a time before deciding to settle for something sedentary and enter the services of the Department of Health and Social Security, where he was to remain for the next eight years.

"I was always bored with the job," he says, "but one way of relieving boredom was to ask to be posted to various parts of the country." As a result, he worked in social security offices in Manchester, Cornwall and Wales, before he finally exchanged the uncongenial task of visiting people to assess their eligibility for supplementary benefit for that of erecting suspended ceilings on a self-employed basis.

Seeing no glittering future in that career either, Gibson joined a TOPS computing course in Liverpool. "The course involved programming an IBM 43/41 in RPG II, which normally should have led to processing business data for a large company rather than working for Imagine Software," says Gibson, "but it also happened to put me in the right place at the right time."

Through the TOPS course, Gibson heard that Mark Butler and Dave Lawson, who had recently set up Imagine Software, were looking for machine code programmers. Although his course did not qualify him for the job, Gibson had taught himself machine code on a ZX-81 he bought in 1980. "I could not afford a 16K RAM pack in those days and with only 1K to play with, there was no choice but to learn machine code," he says.

Called for interview, Gibson was asked if he could produce a fully-fledged game for the Spectrum in the next month. "I did not know what to say," he recalls. "I had no idea whether I could do it or not." After some hesitation, he decided it was worth trying and set to work on Molar Maul, an idea which had grown out of the dental treatment both Butler and Lawson were receiving at the time. The game did well and Gibson has never looked back.

Since he joined Imagine Software at the beginning of 1983, Gibson has seen the company grow beyond his wildest predictions. From the original team of six, including himself and the celebrated Eugene Evans, it now employs 100 people, of whom 28 are full-time programmers, and has spread to three sleek buildings in the centre of Liverpool.

Fast cars are almost a company trademark and a fleet of Ferraris, Porsches and Lotuses indicates the presence of top Imagine programmers or directors. Gibson's Porsche was a bonus for completing Stonkers in a gruelling two months.

Gibson on the look-out for software bandits at 12 o'clock high? |

Imagine Software also boasts art and music departments to help with the graphics and sound of its programs. "It's very pleasant," says Gibson. "I had only to produce the code for Stonkers instead of doing everything myself, as I used to do."

The idea for Stonkers came from Lawson, who suggested it on the grounds that Imagine had never produced a war game. The emphasis was to be on graphics and real-time action to distinguish the game from simpler versions produced by other companies. Gibson's research on the project was limited.

"I based it on TV and film documentaries, some war games magazines lent to me by a fellow programmer who is interested in those things, and plain common sense. The complexity of the strategy was in any case restricted to what I could fit into the computer memory," he says.

Gibson wrote the program on a company Sage IV, which has 1MB of memory. "It was wonderful to be able to store everything on one disc, rather than many different ones on which people made their jam sandwiches," he says. Before the Sage IV, he was using an Apple 256K and says he has never programmed directly on the Spectrum.

To plot the map for Stonkers, Gibson and Imagine artist Paul Lindale used a sheet of graph paper, or rather several stuck together, measuring 13ft. by 8ft. The graphics for the map and its large-scale segments took up 21K of memory and Gibson used every available remaining byte, plus a few more which he was able to squeeze from the machine by juggling with sections of the program, for the strategy and action. "That is why the game has no catchy tunes or fancy title screen. There simply was no room."

Gibson says he would have enjoyed writing Stonkers for the QL which would have allowed a more complex game than is possible for the Spectrum. He foresees a spate of games for the QL as soon as it becomes readily available.

"Certainly Imagine would have no difficulty in adapting to the QL, although I do not think we or other companies would cease to produce Spectrum games. The Spectrum is still the chief money-spinner for software houses."With another programmer, Ian Wetherby, Gibson is working on a new Spectrum game, Bandersnatch, which is due to appear at the end of May. It is already being billed as a "megagame" and Gibson will say no more about it than that it will be several types of game rolled into one and that "it will look and sound fantastic."

In spite of the many changes at Imagine Software in the short time Gibson has worked there, he still finds it provides "a great working environment. I am working with friends and being paid for something I am good at and enjoy doing. I also feel fortunate at my age to be at the start of something so new and exciting." A prey to constant jokes on the subject of his advanced years and decrepitude, Gibson explains the fact that most programmers are so much younger than himself by saying:

"They are the ones who like playing the games, so it is natural for them to be involved in writing them." He claims that he has no aptitude for playing computer games - "a 17-year-old like Eugene Evans can play the games I have written better than I can," he says. He attributes his programming skill to sheer patience and persistence.

Although Gibson thinks the games boom is bound to level-out in time, he sees no end to it in the near future. He also thinks that computers like the QL will become part of people's homes - not just for filing, word processing, accounting and the like, but for things like controlling lights, television sets and central heating.

Gibson frequently works late into the night, sometimes for days at a stretch where there is a deadline to be met, so that he has little time for outside interests, but he likes marquetry.

He recalls that while still at school he played with a rock group called Mud. He left the group to go to college, while they made a series of hits. "I often wondered whether I had done the right thing but it all seems to have come out right in the end," he says. "My mother would say it was fate. Perhaps she is right."