| Hit Squad |

Nicole Segre talks to Bob Hamilton

TO SAY that things move fast in the software industry is scarcely a revelation but Bob Hamilton's career in the last year is a striking illustration of that oft-repeated fact. Since April he has transformed himself from a small cog in the wheels of a large, well-established company into a best-selling games author, co-director of a flourishing software company and, in his own words, "a very lucky man."

The program for which Hamilton, now 28 years old, is best-known is The Pyramid, which has loomed large on the software charts since it was released in October. Described by its author as an arcade-style adventure, the game presents the player with 120 chambers stacked in pyramid formation and inhabited by a variety of monsters such as extra-terrestrial tweezers, galactic strawberries and mutant eyes.

The player's aim is to guide the hero Ziggy in his exploratory capsule from the top level of the pyramid down to its base, zapping the aliens in each chamber with his little laser and collecting the crystal which will enable him to escape through one of the exits into the chamber below.

Several aspects of the game make it one to be played for hours, if not days or weeks. Once you have negotiated the 15 levels successfully, each more difficult than the last, you can play again to improve your score by achieving the same feat in a shorter time, or concentrate on choosing a different route through the chambers with their varying sets of weird and wonderful aliens.

Whenever you have dealt with one chamber, the screen displays a picture of the outside of the pyramid, with your position shown in red - not only a useful guide but a convenient pause in which to rest or perhaps take refreshment before resuming play. Completing the pyramid also gives you a series of numbers which make up a puzzle, with a cash prize offered for the first players to send the missing numbers.

Finally, as in his earlier games, Hamilton has incorporated a code, which only he can interpret, to check the authenticity of the high scores players claim to have achieved.

The pyramid formed the peak of a brief climb in programming which began when Hamilton decided to buy his two younger brothers, then aged 14 and 16, a Spectrum. At the time he was working on the software of an aircraft databus project at Smiths Industries Aerospace and Defence, just outside Cheltenham. Because of a holiday he had planned which failed to materialise, he was at home for two weeks and began to play with the Spectrum. "I was amazed," he says. "I thought it was just as good as all the advanced computer equipment I was using at work."

He was less impressed, however, with the standard of the games he had also bought for his brothers and was soon convinced that he could do better. Less confident of his business abilities than of his programming, he suggested to a friend and colleague, Paul Dyer, that the two of them form a partnership to market Spectrum software.

The result was the new firm of Quest, formed in April, 1983, which later changed its name to Fantasy Software. Hamilton's first production for the fledgling company was a game called Black Hole, which he followed with a second called Violent Universe. Both were simple arcade games of the space invaders type and both sold steadily without creating a great sensation.

It was the appearance of a smash hit from the new firm of Ultimate in the summer of 1983 which made Hamilton change course. The game was Jet-Pac and the quality and smoothness of its graphics convinced Hamilton that he would have to produce something more complex, with more sophisticated graphics techniques, if he was to make a real impact on the market.

"I started with the idea of a pyramid," he says, "and the game grew from there." He acknowledges freely that his two brothers, his girlfriend, his girlfriend's flatmate, his partner Dyer, and their secretary Anne all contributed suggestions, encouragement and sustaining cups of tea towards the successful completion of the game.

While the graphics of The Pyramid are accomplished, Hamilton prides himself chiefly on the game's playability. Its sequel, Doomsday Castle, has, in the opinion of Dyer, less playability and superior graphics. In the same vein as The Pyramid, Doomsday Castle again stars Ziggy, who this time battles against the evil Scarthax, the Garthrogs, the Orphacs, the kamikaze Urks and the "phenomenally nasty" Googly bird.

Even Hamilton has difficulty in saving the universe from these fiends but he thinks that programming a game is a hindrance to playing it skilfully. "To be a good player," he says, "you need a good deal of concentration as well as enthusiasm. Once you have spent many laborious hours programming a game, much of the enthusiasm has gone."

From small beginnings, the firm of Fantasy Software has remained small and both directors plan to keep it that way. "We'd rather produce three or four really good games in a year and keep down our overheads than produce 30 or 40 games of which only one of two will really sell," says Dyer.

The company still consists only of the two partners, the secretary, and one full-time programmer, John White, employed in December to translate The Pyramid for the Commodore 64. Eventually the aim is for Fantasy to produce all its games for that machine and the Spectrum simultaneously.

One of the benefits of remaining small and informal is that it allows Fantasy to keep close links with its clientele. Several files in the Cheltenham office bulge with the letters received at the rate of around 80 a week from grateful young customers. The two directors also produce a newsletter which publishes, among other things, the high scores sent by the players of the various games, duly decoded and checked by Hamilton.

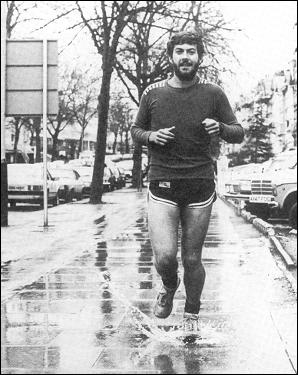

The firm's flexible structure also allows Hamilton to work whenever he chooses, a great advantage compared to his former life as a company employee. While Dyer handles sales, advertising, distribution and other such weighty matters during normal business hours, Hamilton prefers to work late into the night - "my best time, he says is between 11pm and 2am" - saving a part of the day for running and other sporting activities.

"It is sad when you see people playing computer games or programming all day long," says Hamilton, who is a great believer in the healthy life. He likes to run anything between three or 50 miles a day over the local hills in training for various cross-country events. He also once ran a 24-hour race, in which contestants run for a day and a night to see who covers the greatest distance, but so far has never taken part in a marathon. "Too short," he says. "They scarcely give you time to get started."

| 'Hamilton is convinced that keeping fit helps him write programs' |

His new life also means that Hamilton can, say, work 14 hours a day for a spell of two months and then have time to enjoy his other favourite activities, potholing and mountaineering. He once tried hang-gliding but a crash on his first attempt discouraged him from further experiments. Most of his mountain climbing is done in North Wales, but the high spot, in both senses, of his year was climbing Mount Kenya at Christmas.

Hamilton is a vegetarian and is convinced that keeping fit helps him to write his programs. "I do some of my best work after a run," he says.

Exercise apart, Hamilton does not know to what his success as a programmer is due. He has a degree in mathematics, but not computer science, and has never been able to draw. "The main thing," he says, "is to get the overall design right so that the game will be easy to program."

Both he and Dyer have high hopes of the next game, which they plan to release in September. It will be a "true adventure" starring Ziggy and possibly some friends, but no other details are being offered. "We cannot reveal more, in case anyone else beats us to it," says Dyer. In the meantime, Hamilton is working on a lighter arcade-style game called Kondore, with bird graphics inspired by his visit to Kenya.

Hamilton writes all his programs using a Spectrum and two Microdrives and has found that a perfectly adequate arrangement so far. "You do not need fancy hardware," he says. "You just have to push the machine to its limits." Nevertheless, he would not say no to a Commodore 64 and is even more anxious to lay his hands on the new Sinclair QL.

"I think the QL will revolutionise the whole concept of computer games," he says. "It is very exciting but, at the same time, I can see myself regretting the days when you could write an excellent game for the Spectrum in a mere two months. The QL will be much more complex."

Hamilton believes he is an unusually fortunate man. He lives in a town he likes which is surrounded by splendid running country and earns a living by doing what he likes best whenever he chooses. Perhaps best of all is the fan mail and the idea that he is pleasing his public. "On Christmas Day, I woke up to the snowy slopes of Mount Kenya and thought of all the children who might at that moment be opening a parcel to find one of my games and I felt absolutely terrific," he says. "All in all, this has been the best year of my life."

If Hamilton's next games prove as popular as in the past, he should have many more happy times ahead.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||