| Hit Squad |

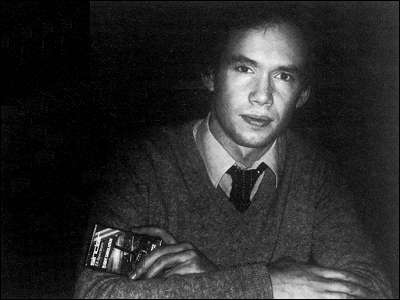

In the first of a series on top programmers. Nicole Segre talks to Charles Davies, the man behind Psion's best-selling game

CHARLES DAVIES, originator of the best-selling Psion program Flight Simulation, is matter-of-fact about the reason for its success. "There is nothing else as good of its kind on the market," he says.

Since it was released early last year, the Spectrum version of the game has climbed the popularity charts, steadily holding top position for many weeks. More than 130,000 copies have been sold; it was translated recently into Spanish and is doing well in the States.

"I do not know who our customers are," says Davies, "but I know that several squadron leaders have written saying how much they liked the program, including one in Greece who wants to use it as a teaching aid in his flying school."

Flight Simulation puts you in the cockpit of a small aircraft. The lower half of the screen shows a complete bank of instrument panels, including altimeter, fuel gauge, airspeed indicator and power gauge, and the upper half of the screen shows the view from the pilot's window.

As you bank, dive or climb, the horizon moves accordingly, as do the three-dimensional runway, landmarks and beacons. Real flight conditions are reproduced faithfully, down to air-flow, angles of approach and rate of climb, and there is a navigational chart to show your position at any stage of the flight.

Even after you have mastered the complicated set of keys representing the various controls, piloting the aircraft from take-off to landing without having a disastrous crash is a difficult task which takes many hours of practice.

"The game teaches the things a pilot needs to know - how to move maps in your head, how to move an aircraft by banking rather than turning, how to climb by increasing power rather than pointing up the nose, and so on," Davies explains.

The authenticity of Flight Simulation, together with its striking graphics, were the result of a great deal of hard work. Davies wrote the original program for the ZX-81 and it took him three months.

"Although flight simulation programs existed on mainframe computers, there was nothing like this for a micro" he says.

"Everything had to be worked-out from first principles, from the aerodynamics to the perspective and 3-D transformations of the view. It took a great deal of very complex mathematical equations to get it correct and I thoroughly enjoyed doing it."

The ZX-81 game proved to be such a success that the rapidly-expanding Psion company soon decided to produce a more elaborate version for the Spectrum. "Everybody took part in that," says Davies.

One programmer, Luigi Ronchetti, worked full-time on the project, under Davies' supervision, for more than four months, and for several months after that eight others took charge of individual parts of the program. "It took one person two weeks to design the dials," Davies recalls.

Now the director of a company which employs 35 people, Davies entered computing via a roundabout route. Looking much younger than his 29 years, Davies was born in Cardiff and attended a Welsh-speaking comprehensive school near Pontypridd. There he quickly showed an aptitude for mathematics and science.

"I was lucky," he says, "since the staff at the school were all very involved in the Welsh-speaking cause and consequently deeply committed to making the school a success. The quality of the teaching was excellent. On the other hand, the science subjects were taught in English, so I did not learn a great deal of Welsh."

After taking mathematics, physics and chemistry at A level, Davies read physics at Imperial College, London. He took a PhD in plasma physics and stayed to do post-doctorate research work at the college. Much of his work was on computers and in his 11 years at the college Davies became thoroughly conversant with Fortran.

His supervisor was David Potter, who in 1981 did what Davies calls "an unheard of thing" - resigned his lectureship to start his own company.

Potter, Psion founder and chairman, had for some time felt disillusioned with university life. "Funds were being withdrawn and there was a general watering down of opportunities," Davies explains. "Anyway, physics has been going downhill since 1927, the time when relativity and quantum theories overturned all the textbooks and created fireworks all round. Nowadays, things happen much more slowly."

Tempted by the challenge of the fast-developing micro scene, as well as by the cut and thrust of the business world, Potter established Psion Computers, first to export the Acorn Atom and the ZX-81 to his native South Africa. Soon afterwards he asked Davies to join him to start producing micro software. Davies accepted the invitation willingly.

"At the time, neither of us knew much about micros," he says, "but we were computer-literate and our experience of bigger machines made it easy to pick things up quickly. We had also used many simulations in our physics research, which no doubt helped set a trend for our future software."

Flight Simulation, produced in a first timid batch of 250 cassettes in September, 1981, not only allowed budding pilots to take to the air but quickly sent the new company soaring. "Last month, the factory with which we started produced 500,000 cassettes for us," says Davies. Psion now sells its entire Spectrum production to Sinclair Research, which deals with all the advertising and distribution of the cassettes.

The arrangement leaves Psion free to concentrate on creating software, which is done by a team of 22 full-time programmers, of whom the youngest is 17 and the oldest 35.

"We like our programmers to have a sound mathematical background," says Davies, "but we do not insist on it. Although training helps to make a good programmer, some people with very little education seem to have an in-born talent for computing and that is good enough for us."

One thing the whole team has in common is that they are all what Davies calls "keyboard junkies."

"Everyone is getting paid for what they love doing anyway, so morale in the company is very high," he says.

At present no new game for the Spectrum is in hand. Maintenance of current production is one priority, which chiefly means eliminating bugs which have been discovered and translating games into other languages for export. The team is also gearing to produce software to run on a variety of machines.

"For the last six months we have been working in C, which we think is the best and fastest of the high-level languages. Certainly it is becoming very popular in computing circles", Davies explains. "We do not drive Porsches," he adds, "but we program on the raciest of computers". The aim is to produce programs in a processor-independent way and the team works on two VAX computers, which Davies terms 'superminis', linked to 15 terminals; the programs are then assembled to run on any particular smaller machine.

"Writing programs in C makes it easy to adapt them very quickly to any computer we like," Davies says.

Although the Spectrum is still top of the Psion list, the company has its eye on the BBC micro and the Commodore 64, and also has plans for business software produced on floppy discs.

"After we have made some progress on all that," Davies says, "we will certainly produce a new Spectrum game but there is no point in bringing out anything mediocre because it will not sell. Our next game has to be something we can make a song and dance about and that will take a few months at least."

Although not an avid games player, Davies loves writing them. He finds the skills they require far more interesting than those needed for serious applications. He also thinks there is plenty of life left in the games market and that the standard of commercially-produced software will continue to rise.

He predicts that by the spring, when the traditional post-Christmas lull in sales takes its full toll, many smaller companies will be forced from the software scene for good.

"People like ourselves have already built a considerable advantage," Davies says. "As well as experience and a solid reputation, we can draw on our software library resources and we also have a good deal of excellent and very expensive equipment with which to work. It is difficult to see how anyone working alone in a front room can compete."

Looking further ahead, Davies is convinced that in five years every home will have a computer, not just to play games but to keep accounts, file, write and edit, interact with other databases, carry out banking transactions and consult expert systems on anything from child care to motor mechanics.

"I can see members of a family arguing about who uses the computer in the same way people argue about which television channel they want to watch now," he says.

His confidence in the future is reflected in the fact that Psion is soon to move from the converted factory in a quiet London mews it occupies to new premises nearby with space for up to 80 people.

In spite of company expansion, Davies remains as closely involved with programming and as enthusiastic as ever. He is at his desk by 8 o'clock in the morning and admits to being "a bit of a workaholic". Although he once liked running and playing squash, he says he now has time for neither, and has not had a holiday for a long time. "Luckily my wife has a demanding career of her own, so she does not mind my absence too much," he says.

Davies has no regrets about giving up the security of an academic career for the pressures of the business world. "The micro scene is full of excitement and vitality," he says. "There are still a tremendous amount of new skills and ideas to develop. This is just the beginning."

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||