| prestel |

There are more than 20 entries for the £1,000 first prize which goes to the designer of best ZX-81/Prestel adaptor. Roger Green tells the story and why there is a need for the adaptor.

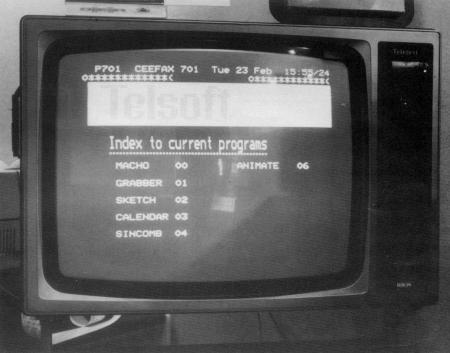

A BRITISH Telecom-endorsed adaptor to allow ZX-81s to run telesoftware programs transmitted by viewdata is to be unveiled at the end of April. The design of the £50 add-on gadget will be the winner of a competition launched at the end of 1981 by Telecom to boost interest among Sinclair users in programs delivered by telephone line through the Prestel viewdata service.

The adaptor is scheduled to make its debut at the April 23-25 Computer Fair in London.

More than 20 competing designs for the unit - which "should be in the spirit of the ZX-81, low-price, practical, robust and efficient" were entered by the March 14 closing date.

Do not expect, however, to be able to look at Prestel information pages if you buy the adaptor. British Telecom telesoftware product manager Tony Sweet expected that the television display circuitry for that would have to be omitted to keep down costs. He explained:

"What is required is a cheap device which will allow the ZX-81 to load and execute programs stored on the Prestel database".

Viewdata was devised 10 years ago as an inexpensive method of selling to the public information stored at dedicated Telecom computer centres. Users dial the computer from a television set, either with built-in additional circuitry or linked to a special adaptor, and select the information they require by pressing buttons on a calculator-like keypad.

The original idea was to generate out-of-office-hours telephone traffic. As such, the service has so far flopped, so now Telecom is seeking new ways to stimulate demand for Prestel. One way is distributing telesoftware programs to owners of personal computers.

The idea of delivering programs in that way is not new in the mainstream computer world. Personal computer users in the U.S. have for some years enjoyed down-loaded programs obtained from special computer services.

The information transmitted by a Prestel computer is a series of 10-bit binary codes - a start bit, seven data bits, an even parity bit and a stop bit. The viewdata decoder strips-out the data bits which can represent one of 128 display or control characters for the television screen. The display characters include all the usual alphanumerics, some special symbols, and a series of shapes which are used to construct the crude graphics which have become the Prestel trademark.

The display area is treated as 24 rows of 40 character positions. The control codes are used to add attributes to the displayed characters, such as background colour or flashing.

In telesoftware, each seven-bit code can be used to represent an instruction of a microcomputer program. A telesoftware adaptor incorporates some buffer memory and a control program to transform them into executable code which will run when loaded into the ZX-81 RAM. In theory, the transformations could be handled by the ZX-81 but in practice that would take too much memory.

The trickiest problem in the design of the adaptor is likely to be the construction of the modem line termination unit which links the device to the telephone network. A viewdata modem employs asymmetric transmission format - 1,200 bits per second from computer to terminal, 75 bits per second for the human button-pushing in the other direction.

The interface with the telephone line will have to be built to rigorous standards of electrical safety to meet the notoriously-strict Telecom rules.

Telesoftware began with some research by the Independent Television Companies Association as part of its Oracle teletext activities.

Teletext is a close relation of viewdata. Information is delivered to modified television sets in the same format as in viewdata but scrambled into television broadcast signals instead of by telephone lines.

Because there is only so much spare capacity in the television signals, there a limit of a few hundred to the number of screens of information which can be delivered by a teletext data store. That limitation is the key difference between teletext and viewdata.

The term telesoftware was coined by a consultant, Will Overington, who had the idea of broadcast "software at a distance" in 1976.

The first telesoftware program transmitted by the Oracle teletext service in February, 1977, for reception on a specially lashed-up Signetics microcomputer system.

The experiments continued later that year with other simple programs, a version of the ubiquitous Mastermind game and a calculate-your-payments mortgage routine.

In parallel, the early demonstrations of what became the Prestel viewdata service included showing some programs initiated from user terminals. Those, too, allowed the calculation of mortgage repayments.

Those early efforts, however, depended on the viewdata computer doing the work, with only rudimentary data submitted from the dumb terminals.

Although the data processing feature was much talked about in the early days of Prestel it was dropped quietly as the system was brought into regular service, because it tied up too much computer power.

By May, 1978, however, the idea was gaining ground of telesoftware transmissions by viewdata to intelligent user terminals. The chairman of CAP, a major British computer programming company, predicted confidently that viewdata would become a major vehicle for software distribution.

It seemed then that teletext telesoftware - because it was free to anyone who had the proper equipment - would emerge as the major medium for programs delivered to domestic users. Commercial data processing users, on the other hand, would buy their programs from a viewdata service which was able to charge them for it.

CAP subsequently put some of its own and £90,000 of Government money into developing the concept. In November, 1978, the company had a full-page advertisement in The Times to inform a wider world about the innovation and to ask: "Has British management the will to exploit it?"

Evidently British management did not. Outside the world of viewdata research, it seemed that no-one wanted to be told about telesoftware.

The following year, public interest was minimal when, in May, telesoftware emerged as part of the ambitious plans of the then Labour Government to educate the nation.

Telesoftware was touted as a method of training the unemployed, through intelligent viewdata sets, to design microcomputers and 64K memory chips.

The initiative disappeared as CAP fell into financial difficulties and decided to stay with more bread-and-butter business activities.

At the end of 1979, another attempt was made to promote the cause of teletext telesoftware when the results were revealed of a collaboration between the Oracle engineers and Mullard, the Dutch-owned electronics manufacturer responsible for most of the world's production of the special chips used in teletext and viewdata decoders.

A prototype intelligent television set was demonstrated running telesoftware programs. As usual, there was one to calculate mortgage repayments and the initiative returned to obscurity.

During all that time, a top-level committee, representing all the interested parties, had been deliberating on the design of an intelligent viewdata terminal. All that emerged, however, was disagreement about the version of computer language in which telesoftware should be written.

The most positive and most promising development in viewdata telesoftware occurred in September, 1980 when the Council for Educational Technology published a recommended format for telesoftware programs stored on Prestel.

The move by British Telecom to initiate the development of a ZX-81 adaptor is in parallel with its other attempts to enlist the help of personal computer enthusiasts to bootstrap the telesoftware concept.

The winning adaptor is to be awarded a £1,000 prize and the possibly more generous carrot of freedom to sell the design to the 250,000 other Sinclair U.K. users.

If only a tiny proportion of ZX-81 owners signed for Prestel, it would make a big increase to the number of users. At present it is no more than 15,000, at least one order of magnitude below the estimates made in the optimistic days of the late 1970s.