| 128 Music |

Bach to the FutureMaking music on the 128. Chris Bourne lets rip on the new sound chip |

|

POOR SOUND has always been a cross Sinclair users have had to bear, right from the early days.

The ZX80 and ZX81 had none at all, while the Spectrum has that godawful Beep, pathetically inadequate for most games and difficult to program. The QL does rather better on noise levels but has one of the most awkward Beeps known to computing man, with masses of numbers after each command to define the sound.

The 128 heralds a new era in the history of Sinclair beeping. For the first time there's a decent sound chip - the same one as is used by Amstrad. Not only does it provide three sound channels through the television speaker, but it's easy to program as well.

This article is designed to take you through programming a simple piece of music on the 128 and on the way demonstrates some of the facilities available. We're going to use a prelude by Bach, who usually sounds quite good on electronic instruments.

First things first, though. How is the sound going to be stored? The 128 uses three strings - a$, b$ and c$ for storing the three separate channels, or voices. A new Basic keyword, Play, produces the sound. The program is therefore going to look like this:

10 LET a$= "some music" 20 LET b$="some more music" 30 LET c$ ="other bits of music" 40 PLAY a$, b$, c$

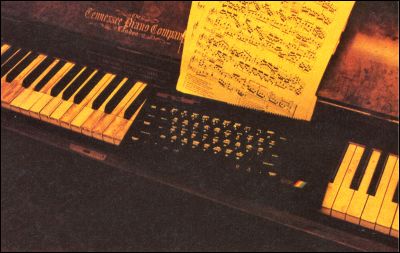

For musicians, figure one shows the first three bars of the music we're going to program. To make things simple, we'll start with c$, which is going to hold the lowest notes in the piece.

Figure 1. The first three bars of a Bach prelude |

The first note is middle C, and is represented by the letter C. But how does the computer know which C to play - the middle one, or an octave higher, or what? There are nine ranges allowed, which overlap and span two octaves each. The bottom half of one range is the upper half of the next, so there are two ranges containing any one note. We want a range with middle C in the middle - octave 4. So the first line in the string is O4C. From now on any notes will be taken from that range - capital letters indicate the upper half and lower case letters the lower half.

So far so good, but this note is in fact a whole minim long - two full beats. If you don't specify the length the computer will play crotchets - half what we want. So we give it the value 7, which means minim: "O4N7C". The N is used to separate two numbers.

The next note is also a minim, so we can write "O4N7CC" without repeating the 7, as all notes will now be minims until that is changed. The next four notes in c$ are also minims - two Cs and two Bs. "O4N7CCCCbb". The small letters for B indicated that we are now in the lower range of octave 4.

The three note ranges used in the program. Notice how A in octave 3 is the same note as a in octave 4. Middle C is in the centre of octave 4 |

That's c$ for the first three bars; b$ holds the notes in the middle - those are more complicated. They're all close to the c$ notes, so we can still use octave 4, but they start with a rest - a piece of silence. The sign for a rest is &. This rest is a semiquaver long - one quarter beat which has the number one, and consequently we get "O4N1&".

After that there's a longer note - a dotted quaver plus a crotchet tied together as one note. That's 1¾ beats, and there's no number for that. But a dotted quaver is four and a crotchet five so "4_5E" means tie the two together on note E, giving us "O4N1&4_5E".

The next note is exactly the same - 13/a beats on E with a rest in front. You don't have to write it all out again, though. Putting a pair of brackets round the bit to be repeated will do the job. "O4(1&4_5E)". Because we've a bracket now between the 4 and 1 at the beginning, we don't need the N to separate the two. The other b$ notes are very similar, giving "O4(1&4_5E)(1&4_5 D)(1&4_5D)". You can't use double brackets here to repeat three or more times, as two brackets means repeat for ever, and we don't want that.

The five basic note values - semibreve, minim, crotchet, quaver and semiquaver. A dotted note would have the same value and half as much again |

The final voice is a$, which starts with a quaver rest followed by six semiquavers. The pattern is repeated throughout, so, just as in b$ we can save space with brackets.

"O5(3&1gCEgCE)(3&1aDFaDF)

(3&1gDFgDF)"

Notice that we started with octave 5 to give a higher range for these upper notes, and the way it switches from lower to upper case letters as the mid-point of the range is passed.

Although a$ is now much longer than b$ it takes the same time to play because the notes are shorter. But how quickly does the computer play the music? If you don't specify a time, you get 120 beats per minute, but you can see an instruction on the music for 108 beats. The command for that is T108. That only needs to be put in a$ - the other channels will keep time with it. So, at the beginning, we get "T108O4(3&1..."

A full listing for the piece, Prelude 1 of the famous 48 Preludes and Fugues by Bach, is given in figure two.

You'll notice a couple of extra symbols have crept into the full listing. Flats and sharps are denoted by $ and # respectively. They apply to the note following.

The letter U turns on various volume effects. There are eight in all, and the listing uses W0, which fades the note out for the duration of X. That gives a sort of old-fashioned piano sound to the notes as they swiftly die away after they have been 'struck'. The other channels are left as they are - like an organ accompaniment.

V15 at the very end of a$ is a simple volume setting. You can go from 0 to 15, 0 being silent. All music is played at the highest volume if V is not set, but here I've used it to cancel the previous effect to keep the final note sounding until the end.

Other sound effects given by U and then W allow the sound to build over the period of X, decay and hold, build and hold, and also to have repeated mixtures of the two. With the right choice of duration, you can get all sorts of sound, ranging from plunkety-plunk piano to noises sounding suspiciously like mouth-organs and mandolins. By combining the effects across all three channels, you can get even weirder sounds.

|