| Programs for Profit |

Writing a good game is just a beginning. Clare Edgeley talks to programmers and publishers, charting the software scene

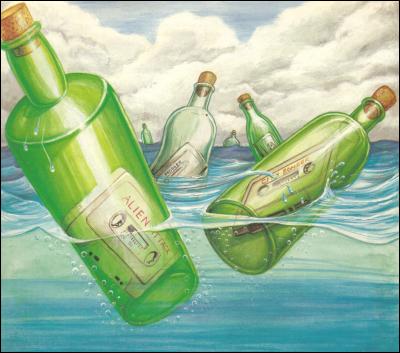

THOSE GOLDEN DAYS when you could buy a personal fleet of flash cars with the massive earnings from Alien Attack are long gone - if indeed they were ever here.

It is not as easy as it was to get your programs accepted by software houses, and even if you are successful, you will be lucky to afford a second-hand C5, let alone the proverbial Porsche. Writing software is as time consuming as ever - getting it published is a different ball game altogether and very frustrating.

A potential hit game has to combine originality with good graphics and instant playability. However, the quality of programming has improved dramatically in the last three years with games like Ultimate's Knight Lore, and it is becoming increasingly difficult for amateur programmers to come up with the goods.

Once a program has been completed to your satisfaction, you will want to send if off for evaluation. Software houses tend to specialise in programs of a particular kind, whether they are arcade games, adventures, simulations, utilities or strategy games. Although many software houses publish programs from several categories, it is best to pick publishers most suited to the software you have written.

Software publishers can also be divided into two further categories those which deal in top of the range games and those which deal with budget software. Again, a number of companies produce both.

Mike Cohen, managing director of Lothlorien says, "Up to a year ago, we were being sent games which we could put out. The market then became more critical and a higher standard is now demanded. Meanwhile, budget software surged forward and youngsters got their games accepted because of the budget ranges."

Andrew Hewson of Hewson Consultants feels strongly against pocket money software. "We're not interested in the budget range because of the aura associated with it." He feels that if a game is good, it deserves to be marketed at a reasonable price.

| "It is easier to get accepted by a budget software house at first" |

Although everything depends on programming quality, it is easier to get your first attempts accepted by a budget software house than one dealing with more complex software.

Two such companies are Mastertronic and Firebird, which publishes its Silver range. "Budget software provides an opportunity for new software writers to enter the market," says James Leavey of Firebird. "We are fairly demanding and look for well programmed, machine code games."

Leavey believes that programmers of the Silver range may one day come up with a game worthy to be sold in the more expensive Gold range. "They've got to start somewhere they are the programmers of the future." And just because a game is sold on a budget label, it does not mean that it will not be successful.

|

Booty has sold over 100,000 units for Firebird and Chiller, Mastertronic's most successful game has sold over 100,000 copies on the Commodore 64 and 30,000 on the Spectrum.

John and Jan Peel of Legend, which produced Valhalla, always come up with their own games ideas and employ a team of in-house programmers.

"Games which people have sent in are not even good enough to return asking for improvements," says Jan Peel. "I can say that the best stuff submitted wasn't too boring." One program submitted was a BMX bike game which had the spectators moving while the bike remained still.

Many larger companies employ teams of in-house programmers, or freelance programming houses, to produce their software and very rarely use programs sent in for evaluation. "Lots of programmers don't have the three arts - programming, music and graphics," explains Ocean's Paul Finnigan. Special teams are put together to work on each game, dealing exclusively with those three areas.

Finnigan continues, "If someone from the outside sent in a good game, we would invite him to come in and produce the game with the team or in some cases give him a job."

"We have all sorts of development equipment," explains Finnigan. "The games are written on an Einstein or Sage and then downloaded to the Spectrum and Commodore 64, where the music and other extras are added."

Software houses tend to receive huge numbers of games for evaluation each month. Many fall by the wayside immediately, either because they lack originality, or because they are unplayable. Companies are not interested in fruit machine games or yet another PacMan, however good.

Mastertronic processes around 200 games a month and in May this year 220 games were looked at. Two games were picked out - one which was almost marketable and one requiring more development. It publishes between four and six games a month, and has 40 or 50 people working on games which are at various stages of completion.

John Maxwell from Mastertronic explains why many games cannot be looked at properly. "We can only spend ten minutes on each and many come in without instructions or any form of documentation and so cannot be evaluated properly." That is especially important if you are submitting an adventure game. Without a map it would be impossible to evaluate within the 10 minutes available.

Howard Gilberts from Gilsoft, the company which has changed adventure writing with The Quill, feels that documentation is essential when sending in a utility program. "Those utilities which rely on a handbook should have a draft of that sent in as well. The handbook should be easily understood, free from mistakes and presented in an interesting way. The handbook is as important as the utility."

When your game has been accepted it is normal procedure to sign a contract with the publishing house concerned. It is always a good idea to have a contract checked by a solicitor but there are a few points you could look out for yourself.

The company will usually buy the licence to market your game, although you will retain the copyright. Check the length of time they will hold that licence - it can vary from one year to an indefinite period.

If possible, ensure that the company you are dealing with is rock solid and not about to go into liquidation. If the company goes bankrupt make sure that the licence reverts to you and not to the liquidator. Then you will be able to resell the game.

Have you sold the licence to your game for European or world rights? An important point - a company might hold only the European rights, yet you will not know whether the game is being sold in the States.

Contracts also state how you are being paid, whether by royalties and an advance, or just a flat payment. Christian Penfold from Automata offers some advice. "Make sure a figure is stated rather than a percentage of the profit. Some software houses are entitled to deduct packaging, advertising, duplication and other costs from the price before royalties are worked out - the percentage is therefore lower than it looks."

Royalties are usually based not on the retail price of the software, but on the sum left after selling the game to a distributor. Distributors will take, on average, a 55 per cent discount.

Royalty payments are usually calculated against the number of units the company expects to sell. If you think your game will sell less than the company has predicted go for a lump sum payment. However, if you feel it will be a success go for royalties, and an advance if possible.

Advances can range from £100 to £2000 and upwards depending on the quality of the game. Royalties can range from 4 per cent to 20 per cent. If you receive a large advance, the chances are that the royalties payments will be lower and vice versa.

Considering the software market has been chaotic over the last year, there is still a surprisingly large number of companies willing to accept games as long as they come up to standard. There is no point sending in a game only good enough for a magazine listing. The software house will not even look at it. If you can come up with the goods - they'll take it.

| ||||||||||