| User of the Month |

AS MORE and more acres of farmland and forest are sacrificed on the altar of industrial development, rescue archaeology becomes increasingly important as a means of documenting Britain's heritage before the bulldozers move in. Lack of public funds usually results in all but a few excavations being carried out primarily by amateur archaeologists motivated solely by a love of history and an apparent ability to wield their trowels tirelessly in pursuit of buried treasures.

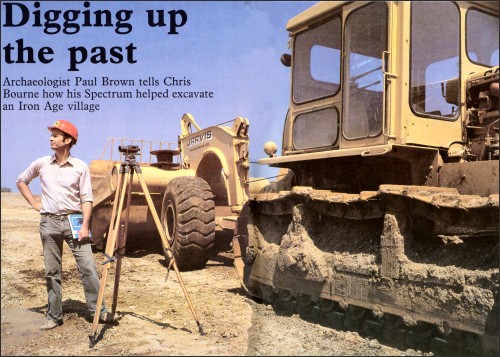

One such archaeologist is Paul Brown, a founder of the Maldon Archaeological Group in Essex. He received an award of £200 recently for the group on the strength of a program he wrote for the 48K Spectrum, Pitcalc, which proved invaluable last year on a particularly troublesome operation.

An area of farmland outside Maldon had been designated for gravel extraction but it was also the site of an Iron Age farm. The overriding factor in rescue archaeology is time - the site had to be excavated literally as the contractors moved in to scoop out the gravel.

While archaeological digs occasionally produce spectacular treasures, one of the most important aspects is not simply concerned with the objects discovered but precisely where they were found. By creating an accurate plan of the site showing the exact position of even the smallest piece of broken pot or bone it is possible to learn a great deal about the site as a whole. The Pitcalc program was written to enable the group to produce that data at high speed, in spite of the special problems involved with gravel pit operation.

The program uses bearings to calculate the position of objects. In the field, Brown takes three or four theodolite bearings on known fixtures and records them in his notebook. They, might be buildings, trees or telegraph poles - anything which stays in one place. The distance between those reference points is measured and entered into the program, which can store details of up to nine reference points to save typing in the same figures over and over again. Because accuracy is so important, the four-bearing program also produces a figure for the limits of accuracy.

Brown bought a Spectrum at Christmas, 1982. He works as a technical officer for British Telecom and says he enjoys learning about electronics matters through practice. "I did not do very well at college," he says. "I prefer learning through playing around."

The main reason for buying the Spectrum was to help with the archaeology group but he also wanted to learn more about computers, as his work did not take him directly into contact with them. "I also bought it for my two-year-old," he says, "but that was an excuse really."

He chose the Spectrum because of its price and adaptability. The decision was influenced by his hopes of writing useful archaeological applications which could then be used by other groups. It seemed sensible to buy a machine which was popular and supported by a range of software if his programs were to be used elsewhere.

"I respect the machine more now I have got to know it", he says. "It was a long time before I wrote the program we use now. It was not easy to program and very time-consuming."

The group has used the £200, which was awarded to it by Lloyds Bank, which has a fund to sponsor independent archaeologists, to buy two Microdrives. "They have made a tremendous difference," says Paul. "Now we can analyse the data in an hour or so. I have been writing programs to make them easier to handle, with single-key entry to any program."

The Microdrives, which the group acquired two months ago before receiving the cheque, were not without problems.

One of the cartridges refused to format and it took more than six weeks to obtain a replacement from Sinclair Research. When the replacement arrived it was equally stubborn. Brown lost an hour's work but he is phlegmatic about such difficulties, believing that the products speak for themselves. "That is why Sinclair can get away with things others cannot," he says.

The Pitcalc program has been expanded from the version used last year on the Lofts Farm dig at Maldon and now includes several refinements. There is a program to calculate the size of ring ditches from measurements on small sections of the ditch, which may be the only remaining features of the original structure, and another program to calculate the distances between the reference points used in the main Pitcalc program.

A final refinement is a program to convert polar co-ordinates into ordinary cartesian co-ordinates so that the results of the survey can be entered easily on a large-scale grid map of the site.

The program is now being sold by the group for £5 and at the awards ceremony it generated considerable interest. "I am surprised at the number of people who have asked about it," Brown says. He is hoping to be able to generate funds for the group by selling the program commercially and believes that as a general trigonometrical calculator it might be of interest to schools.

"I like to manipulate programs to make them work the way I want them to do" he says. "I hope people will be able to break into Pitcalc and write their own variations".

He is looking into the possibility of setting up a user club at Maldon and even writing games programs based on the town and its history, perhaps for the educational market, as a means of promoting indirectly the archaeological significance of the area, which has been occupied continuously since prehistoric times.

Brown is married with a young son, Jonathan. Unlike many women who find their husbands' addiction to microcomputing isolates them, with Elaine Brown the Pitcalc program has had the reverse effect, eliminating the time-consuming drudgery of calculations when they return home from the dig.

She uses the computer with Jonathan, who has some spelling and counting programs, although she recalls one disaster: "Paul was working late one night", she says, "and I stayed up to keep him company. Unfortunately I switched off the program and all the work was lost. Luckily he is one of those terribly placid people."

She shares her husband's keen interest in archaeology and is an active member of the group. She says Paul frequently wakes at 5am to go to the site and excavate before workmen arrive to start digging the gravel. He also goes every lunchtime and after work.

"The contractors were very helpful," she says, lest you should imagine there is conflict between the industry and the archaeologists. "They have given us money and are very good about back-filling". Back-filling is the process of filling in the pits to repair the landscape after the gravel has been extracted.

When the mechanical monsters arrive they first scrape the topsoil to lay the gravel bare. At that point the archaeologists move in to check for possible finds. There the program is particularly useful, as not only are the contractors anxious to press ahead but the gravel moves as the digging continues and it is very difficult to measure distances using traditional marker pegs and tapes.

"Obviously they have to meet their schedule," says Elaine. "We work with the machine drivers wherever possible." Sometimes they lose finds nevertheless and Elaine recalls a moment when she picked up one part of a pot and then had to watch as the machines obliterated the remainder of it.

Whether or not Pitcalc is a success with other groups, Brown is already working on more applications for the Spectrum. At present the group is using the machine to make labels and also as an advertising aid.

"To have to go to a shop and use a photocopier is time-consuming and awkward," he says. "I always have a project I wanted to do and I am now working on data storage programs with the Microdrives."

He explains that the Maldon group is primarily a collection of people with a shared interest in the history of the town but they all have their personal enthusiasms in archaeology. Although the others are not very interested in computing the group has been keeping an eye on new techniques and technological developments in archaeology.

Even though the program was not used during the early part of the dig, because it had not been finished, Brown says it would not have been possible to produce such a comprehensive plan of the site without it - certainly not quickly.

With many people seeing the advent of the new technology as a force which will obliterate traditional ways of working and living, it is pleasing to find one man who has put the micro to work to help preserve our heritage and make it easier for archaeologists to dig up and interpret finds, rather than spending days and weeks compiling tables of statistics.