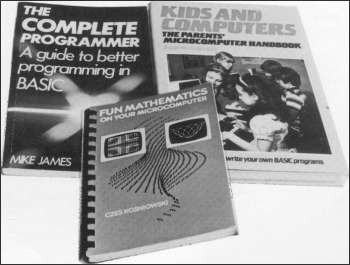

| Books |

Many parents do not understand children's interest in computers. John Gilbert reviews a publication aimed at helping them

THE SPECTRUM and ZX-81 until now have been children's playthings so far as many parents are concerned. With the availability of a new book which aims to provide an introduction to computers for parents, that situation may change.

The book is Kids and Computers, The Parents' Microcomputer Handbook, by Eugene Galanter. It first takes an adult through the history of computing to explain why computers are so important and what effect they have in our lives.

The opening chapters state that if children are not computer literate to some degree they are illiterate as far as education in Britain is concerned. That is true to some extent and the author argues the case strongly in the chapters which follow.

He stresses the good points of using a computer. Using a keyboard will prepare a child for typing skills which may be required in later life. They will learn that the computer does not tolerate spelling mistakes in programs, so the child will have to spell correctly. The child must also solve problems in small, logical steps.

The book shows how the parent can become involved in the learning process without taking away the feeling of achievement from the child. There is even a computer development chart showing the average ages at which children assimilate computer skills. The learning process can start at about five years of age when the child becomes used to the keyboard and is able to locate characters on it.

It is an excellent introduction for parents who want to know why their children spend all their spare time in the bedroom in front of a computer keyboard and screen. It is available from Kingfisher Books and is an inexpensive hardback costing £5.95.

Fun Mathematics on your Microcomputer continues the educational theme. It is by Czes Kosniowski and aims to show that mathematics can be entertaining.

Some of the explanations are a little difficult to understand and the general style of the book would make it of more interest to college or university students than to schoolchildren or adults with only a rudimentary understanding of mathematics. That is a pity as many of the ideas of the author are of interest to anyone who owns a computer.

The most interesting chapters cover games playing and graphics. If you are interested in gaming strategy or how to draw three-dimensional shapes, the book is for you.

Kosniowski shows that almost every operation performed by a computer is in some way governed by numbers and that it is with equations and formulae that games and graphics are designed. The book, from Cambridge University Press, costs £4.95.

The Complete Programmer, by Mike James, is another book which professes to show the beginner the difference between good and bad programming practice. It is different from most of the others which seem to be written by people who know a good deal about theory but not so much about practice.

James makes no claim about being an expert in programming techniques, although he obviously is, and even stresses that there is no such thing as good programming technique, only preferred.

If a reader can tolerate the dense style of the author the text is guaranteed to increase knowledge of programming and therefore make programs easier and more fun to write. On top of that your programs will run faster than they used to do and the listings will be easier to understand.

The Complete Programmer is one book on 'better' programming technique which can be thoroughly recommended. James' style is slightly heavy-going and some of his arguments could be compressed from a page to a paragraph but the book is worth having as a reference or learning manual.

It costs £5.95 and can be obtained from Granada Publishing. It is slightly expensive but the information it contains is worth the extra money.