| inside sinclair |

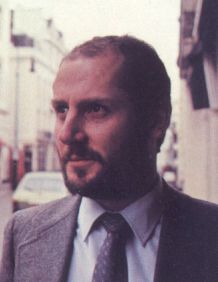

Nigel Searle looks to the future

IN 1964, as an undergraduate, I saw a computer for the first time. It was an IBM 1620. I spent a good deal of time, much of it late at night, using that machine during the next two years. I realised that the IBM 1620 represented a considerable advance over the technologically primitive computers of the late 1940s and 1950s and I gave some thought to the directions in which future improvements might lead.

I did not imagine, however, that 18 years later a small company called Sinclair Research would have sold more than one million computers and that the biggest-selling model, the ZX-81, would offer computer power similar to that of the IBM 1620 for less than £50. Still less did I imagine that I might be involved in running that company.

Obviously, the 18-year period from 1964 to 1982 has been one of enormous change. Another 18 years will take us to 2000, a suitable target for predictions about the future. What will personal computers be like in 2000? For what will they be used?

If Sinclair Research has anything to do with it, as it intends it should. The personal computer of the future will be small and inexpensive. Sufficiently inexpensive that anyone who has a use for one, and that might be everyone, will be able to afford it. As for size, it will certainly fit in your pocket and it may even be as small as a credit card.

There will be no keyboard. Instead you will communicate with your computer by speaking to it. You may have to adhere more strictly to rules of grammar and pronunciation than in human-to-human speech but even that requirement eventually will disappear and, as Sinclair advertisements for the ZX-81 say, "Inside a day, you'll be talking to it like a friend".

You will also be listening to it like a friend. A principal means of computer-to-human communication will by synthesised speech. It will also employ a flat, colour, high resolution display to output information in graphic and alphanumeric form.

That small device will have a massive memory containing just about anything you might want to know in the way of general data about the rest of the world, as well as any amount of personal information which you have instructed it to remember for you.

| 'You will communicate with your computer by talking to it' |

The resident software in your personal computer will enable it to organise its memory so that accurate, rapid retrieval is possible. It will also be able to reason - to make logical deductions from what it knows - and also to induce new facts, attempt to verify them, and to assess their plausibility.

In terms of intelligence, it will be human-like but will far surpass the speed and capacity of the human brain. It will lack a body, consciousness and emotion. The latter two might be simulated eventually but why one would want a machine which was, or appeared to be, conscious and have emotions is not clear. On top of that the personal computer of 2000 will also serve as a portable telephone, enabling you to communicate with any other computer owner anywhere in the world.

Perhaps more important, you will be able to talk not just to another person but to his computer; and your computer will be able to communicate directly with his computer, perhaps without either of you being aware you are doing so.

A typical use might go something like this:

Fred to computer: "What time is Bill getting back today?"

Computer: "Bill who?"

Fred: "My brother Bill".

Computer searches its memory for information about brother Bill's travel plans for today.

Finding no such information in its memory, Fred's computer sends a message via satellite to Bill's computer, which recognises Fred's code number and gives him access to the semi-private parts of its memory.

Bill has not told his computer when he is travelling, so:

Bill's computer to Fred's: "I don't know; do you want me to ask him?"

Fred's computer: "Yes, please"

These are not spoken but digitally-encoded communications.

I hope Sinclair User will let me write a second article in 2000 to review the next 18 years. Perhaps I shall be lying on a beach somewhere and I will just ask my computer to write it.

Nigel Searle is head of the computer division of Sinclair Research.