| inside sinclair |

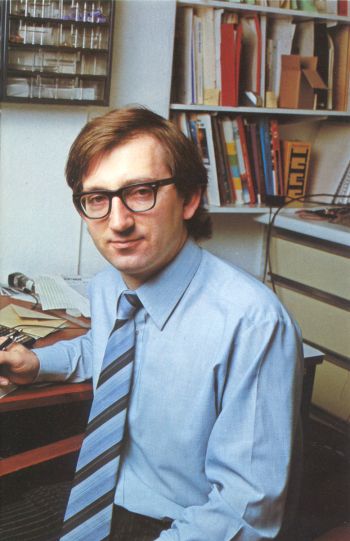

Jim Westwood has been with Clive Sinclair since his earliest days and still flinches at some of his ideas. Claudia Cooke speaks to him in Cambridge

ONE OF Jim Westwood's first pieces of engineering wizardry was the contraption which enabled him to carry-out soldering work from the comfort of his bed. Were it not for the fact that he was only 12 years old at the time, that might be mistaken for the sign of an extremely lazy character. As it is, it merely emphasises the trait of ingenuity which has helped him during his 20-year working relationship with Clive Sinclair.

| 'When you are working unconventionally I don't think training matters very much' |

During those two decades, he has had a hand in such innovative products as the Sinclair pocket calculator, the three more recent computers and the promised flat-tube TV, not to mention the transistor radios and hi-fi equipment of the early days.

Today, at 34, he is known as senior, or chief engineer, with Sinclair Research, a role which combines engineering and management skills.

It is a far cry from the early 1960s when he joined Clive Sinclair and one secretary straight from school and relied on trial and error, as much as natural aptitude, to take him through his first days as a technician.

"Engineering of a kind was always my hobby, even when I was very young. Wherever I went you could be sure of finding a trail of broken torches in my wake. I had to take everything to pieces and gradually I was able to put it together again", he says.

It is that consistent, if unorthodox, philosophy which stood him in good stead for so many years and ensured that the products in which he had a hand were always at the forefront of technology.

"I think it must be unusual to find someone like me in a fairly senior position without formal training", he says modestly, "but when you are always working unconventionally, as we are at Sinclair Research, I don't think training matters very much. Aptitude is more important".

From his small office in Cambridge, surrounded by an orderly chaos of electronic equipment, he seldom works on fewer than three ideas at a time. Of those, few come to fruition and only a handful reach initial design stages.

"The most difficult part is deciding what we want to achieve in the first place. We start with a mess which we call a breadboard. That has a very basic outline of our concept.

"All of us here have electronics in our bones and so when we first discuss an idea we know roughly its chances. Because we always produce 'firsts' we can be reasonably sure there will be no competition.

The real worry is always whether it will catch on. You might feel sure there is a certain demand in the market but you are never sure just how it will sell".

Westwood admits that he still flinches at the sound of some of Clive's ideas but adds: "It's a challenge managing to achieve something without using expensive components and I like that challenge.

"Of all the products with which I have been involved I think the ZX-80 is my favourite. It was a real breakthrough in the use of cheap components. It is something which ought to be in the Ark by now but I am still proud of it".

Westwood is a modest and unassuming man, dismissing his early role at Sinclair simply as a matter of fiddling with the components and trying to get the thing working.

His confidence grows as he talks of Sinclair generally and it is clear that he recognises the combined talent in the company, a team which would be incomplete without him.

"We are always surprised at how long it takes the rest of the world to catch up with us. After working with Clive for years, you learn that it is worth trying to do things other than the straightforward way. It has amazing benefits. All our products show imagination and inventiveness; they make other people envy us and want to work for us.

"We spent a long time getting all the people together and now we have a very strong team, which is one of the main reasons for our success, in my view". Westwood, who is married to a former teacher and has four children under the age of 10, is adamant that his family will not be reared on a diet of TV games.

A seemingly bad advertisement, perhaps, for his work, but he is already introducing his children to the concept of computers as an aid to living - and they love it.

"My only adverse reaction to the whole thing is that the instruction manuals leave much to be desired when you are trying to teach children".

| 'We are always surprised at how long it takes the rest of the world to catch up with us' |

Aside from the sheer technology of his job, he has become involved increasingly in management, taking part in the decision-making and ensuring that ideas are carried through the system.

He enjoys decision-making and the follow-up process, including the field trials which, for the flat-tube TV, will take him round the world.

"There has not been a great deal of travelling so far. Of course, I go to Dundee often and our private aircraft has made a huge difference to that; it beats the sleeper anyway.

"It will be another challenge to work on the field trials. We will have to set up small laboratories or take the equipment with us, trying it and perhaps modifying it slightly to suit the various surroundings".

Ask what follows the flat-tube TV and Westwood is overcome by a sudden vagueness, at odds with the forthcoming nature of the of the interview so far. He may be untrained, he may be shy, but Westwood knows when he is being tapped for a secret; and, like all good engineers, he is giving away nothing.