| helpline |

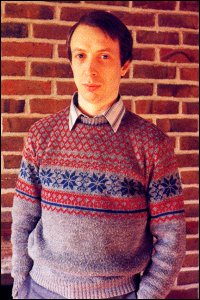

Andrew Hewson |

In this column Andrew Hewson, author of Hints & Tips for the ZX-80 and Hints & Tips for the ZX-81, answers your questions on hardware and software for Sinclair ZX computers.

I HAVE had many letters in recent weeks asking about the methods used by the ZX-81 to store and display numbers and so I have devoted this month's column to the topic.

The machine uses one of three methods, depending on the context. The first is the floating point method which is used for all Basic variables and all calculations involving Basic variables. All numbers held using the technique occupy five bytes each. The second method is used internally by the Z-80 microprocessor which drives the ZX-81 and can be used for whole numbers only.

Each number occupies only two bytes and a variation of the method is used to store the line numbers at the beginning of each Basic program line. To communicate to the user the ZX-81 uses a third method, the character form, in which each decimal digit, and the decimal point, occupies one byte each. All the questions this month concern the floating point method. The first is from James Tucker, who asks:

What does floating point arithmetic mean? Why use it? Would it not be easier to use the decimal system?

The use of floating point arithmetic implies that numbers are stored and manipulated as a mantissa, which contains the digits in the number, and an exponent, which indicates the position of the decimal point. It is relatively easy to convert decimal numbers into a decimal floating point representation and some calculators can display decimal numbers in that form. The calculator manufacturers refer to the form as scientific notation.

The great advantage of scientific notation is that very large numbers, or numbers which are very close to zero, can be written approximately using a limited number of digits. Thus a calculator which can display only eight digits at a time can display a number larger than 99,999,999 using scientific instead of ordinary notation.

For example, the distance from the earth to the sun is about 5,892,480,000,000 inches. Thirteen digits are required to write the number in ordinary notation but when it is re-written in its scientific form as 5.89248x1012 only eight digits are required - neglecting the x10 which is common to all numbers written in that way. The mantissa is 589248 and the exponent is 12.

The exponent, by the way, means "imagine that the decimal point is to the right of the left-most digit of the mantissa - i.e., between the 5 and the 8. Now move the point 12 places to the right, filling spaces with zeros if necessary".

The scientific form, of course, is not accurate because only eight digits, of which six only are in the mantissa, are allowed, whereas in the ordinary form 13 are available, although in our example the extra digits are all zeros.

We count in tens and so calculators display numbers in decimal for our convenience. Digital computers count in binary as explained in chapter 24 of the ZX-81 Basic programming manual but the principle of floating point binary representation is the same as that of decimal scientific notation. The ZX-81 uses a string of seven zeros and one for the exponent - i.e., one byte with one bit reserved for the sign of the exponent - and a string of 31 zeros and ones for the mantissa - four bytes with one bit used for the sign of the mantissa.

Floating point arithmetic is used because it enables a large range of numbers to be stored in five bytes with only a small loss in accuracy.

Numbers as big as 1038 - one followed by 38 zeros - can be stored, although only the first nine digits or so are accurate. If integer arithmetic were used, then the biggest number which could be stored in the same space would be 1,099,511,627,776 but all 13 digits would be accurate.

How are numbers stored in the ZX-81? Please explain how the five-byte representation of a number is obtained, writes Peter Stern.

The following program prints the floating point form of a number entered by the user at line 20:

10 PRINT "ENTER A NUMBER" 20 INPUT I 30 PRINT,,"THE ZX81 REPRESENTS":I:"BY" 40 FOR J=1 TO 5 50 PRINT PEEK (PEEK 16400+256*PEEK 16401+J);""; 60 NEXT J 70 PRINT 80 PAUSE 500 90 CLS 100 RUN

The ZX-81 stores the values of all Basic variables in the variables areas and the address of the beginning of the variables area is held in VARS at locations 16400 and 16401 - see chapter 28 of the ZX-81 manual. Thus the loop at lines 40 to 60 prints the contents of the five bytes which hold the floating point version of the number entered.

The first of the five bytes is the exponent, E, and the remaining four bytes, A, B, C, D represents the mantissa. If the original number is positive, A lies in the range 0 to 127. If it is negative, A lies between 128 and 255.

The following program reconstructs a number from its Sinclair floating point form:

10 PRINT "ENTER THE EXPONENT AND THE FOUR NUMBERS OF THE MANTISSA, ALL ENTRIES TO LIE BETWEEN 0 AND 255 INCLUSIVE" 20 INPUT E 30 INPUT A 40 INPUT B 50 INPUT C 60 INPUT D 70 INPUT,,"EXPONENT=",E,"MANTISSA=",A,,B,,C,,D 80 PRINT,,"THE NUMBER=";(2*(A<128)-1)*2**(E-160) *(((256*(A+128*(A<128))+B)*256+C)*256+D)

Try those two programs for a variety of numbers. You will see that the exponent is about 128 for numbers close to 1 and -1; that numbers close to 0 have small exponents; and that large positive and large negative numbers have large exponents.

It is also noticeable that the value of the fourth byte, D, has little or no effect on the value printed by the second program. In computer jargon D is called the least significant byte. The ZX-81 prints results to eight decimal figures at most, rounding the result if necessary, although calculations are made to somewhat greater accuracy.

The final question is from Roger Hurr. He writes: I am writing a program to test my son's arithmetic but I have found that my ZX-81 sometimes gets the answer wrong. I know that some early ZX-81 ROMs made an error with the square of 0.25 but my machine does not make that mistake. Is this another bug?

He sent his program and it became apparent quickly that the fault lay with his program and not with his ZX-81. The routine which was at fault set a problem in division and then compared the user's reply to the result calculated by the ZX-81. Unfortunately for him the routine often rejected correct replies.

It is often impossible to convert a decimal number exactly to a binary floating point number and that was the source of Roger's problem. An analogous difficulty can occur when converting some fractions into decimal - we are all familiar with the fact that one-third cannot be written as an exact decimal. The program was rejecting the user's reply even when it differed by only a tiny amount from the calculated result.

The following program asks you to enter a number, divide it by 10 and enter the result. It then prints the floating point representation of your result and its own result for the same calculation. If you run the program a few times you will see that your answer and the answer produced by the ZX-81 often differ by one in the least significant digit of the mantissa.

10 LET N=500 20 CLS 30 PRINT "ENTER A NUMBER" 40 INPUT I 50 PRINT,,"YOU ENTERED";I 60 PRINT,,"DIVIDE";I;BY 10" 70 PRINT "ENTER THE RESULT" 80 INPUT J 90 PRINT,,"YOU ENTERED";J 100 LET K=I/10 110 IF ABS(K-J)<.0001*K THEN GO TO 170 120 PRINT,,"WRONG" 130 PRINT I;"DIVIDED BY 10 DOES NOT EQUAL";J 140 PRINT "TRY AGAIN" 150 PAUSE N 160 RUN 170 PRINT,,"RIGHT" 180 PRINT I;"/10=";J 190 PAUSE N 200 CLS 210 PRINT,,"THE ZX81 REPRESENTS";J;"BY" 220 LET M=13 230 GO SUB 300 240 PRINT,,"AND";I;"/10 BY" 250 LET M=19 260 GO SUB 300 270 PAUSE N 280 RUN 300 FOR L=M TO M+4 310 PRINT PEEK(PEEK 16400+256*PEEK 16401+L);""; 320 NEXT L 330 PRINT 340 RETURN

If you wish to avoid problems of that nature then you should alter statements like

IF K=J THEN GO TO 170 to IF ABS(K-J)<.0001*K THEN GO TO 170

In the first case the program will jump to line 170 only if K and J are identical down to the last digit. In the second case, the jump will be made if the difference between K and J is less than .01 percent.

© Copyright Hewson Consultants 1982